The lithium-ion battery revolution has received high-profile recognition from academia with the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarding this year’s Nobel Prize for chemistry to three scientists that played a pioneering role in developing the underlying technology that makes lithium-ion batteries possible – almost 50 years after conducting their research.

The world-famous prize was awarded to John Goodenough from the University of Texas, Akira Yoshino from chemical company Asahi Kasei and Mejo University and – most notably for Australian investors – to Stanley Whittingham who is currently an executive director of lithium-ion battery producer Magnis Energy Technologies (ASX: MNS).

Magnis chairman Frank Poullas welcomed the news by saying: “To have a Nobel laureate as a director, and one with such relevant sector expertise, is a great privilege, not only for Magnis but for the whole investing community in Australia”.

At 97-years of age, Mr Goodenough received the award, making him the oldest laureate to receive a Nobel Prize.

Each scientist will receive equal shares of the 9 million Swedish kronor (A$1.3 million) prize and are set to become the officially recognised pioneers of a technology that is actively transforming multiple industries and society as a whole.

The award was announced on Wednesday last week with the world’s media quickly sent into a frenzy as a result.

“They [lithium-ion batteries] have laid the foundation of a wireless, fossil-fuel-free society, and are of the greatest benefit to humankind,” the academy said.

Going commercial

Lithium-ion batteries are on course to deliver a seismic shift in global energy given their ability to power increasingly more devices including mobile phones, laptops and electric vehicles.

Moreover, lithium is rapidly becoming the new go-to material that could potentially usher in a shift away from carbon-based fossil fuels towards cleaner energy sources.

Over the past decade, dozens of companies have come to the fore to commercialise lithium and offer a wide variety of products that are already transforming modern society.

Despite being commercialised since 1991, lithium-ion batteries are only now making their surge towards ubiquity.

Most notably, the likes of Tesla, Panasonic and Samsung are producing significant amounts of products powered by lithium-ion batteries including electric cars, communication devices and alternative power sources to provide energy for homes and businesses.

Lithium-ion battery designs

Lithium was discovered in 1817 when Swedish chemists Johan August Arfwedson and Jöns Jacob Berzelius purified it out of a mineral sample from the Utö mine, in the Stockholm archipelago.

Berzelius named the new element “lithos”, the Greek word for stone.

Lithium is the lightest solid element but is unstable and reactive with air. However, its weakness is also its biggest strength.

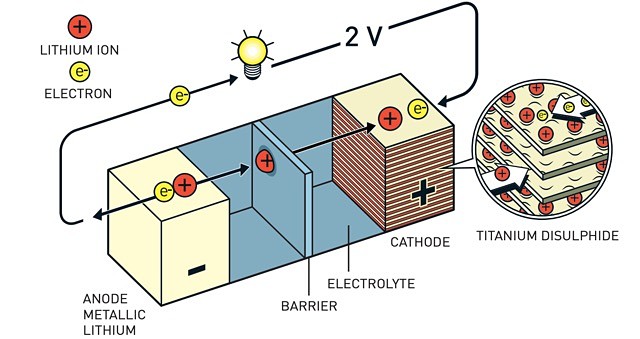

Lithium’s reactivity has meant it was the perfect candidate to be able to contain charged ions in a process called “intercalation”. And it was Mr Whittingham who used lithium’s enormous drive in the 1970s to release its outer electron when he developed the first functional lithium battery around 50 years ago.

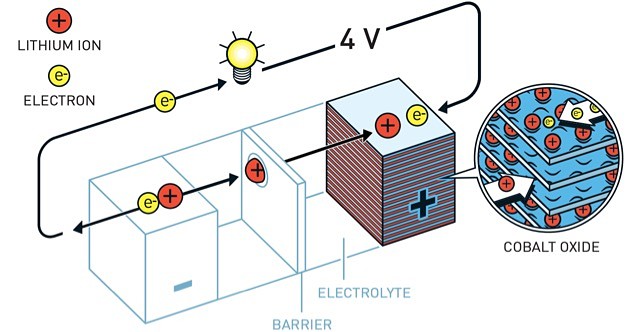

In 1980, Mr Goodenough doubled the battery’s potential, creating the right conditions for a vastly more powerful and useful battery.

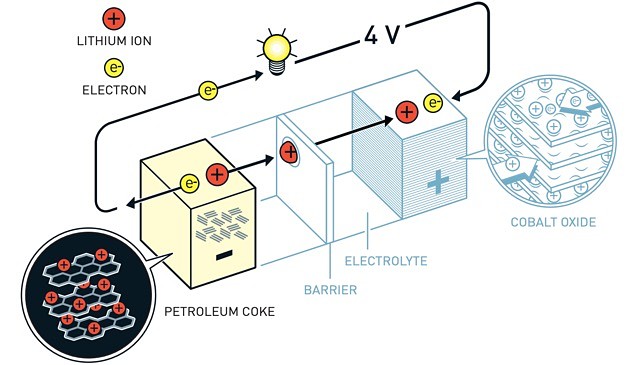

Five years later, Mr Yoshino succeeded in eliminating pure lithium from the battery through re-focusing development on lithium ions which are safer than pure lithium.

This discovery proved to a masterstroke that made lithium-powered batteries workable in practice and set the stage for multifaceted commercial applications.

From lab to market

With the technology successfully developed in the 70s and 80s, there were still several factors that had to be addressed before lithium-ion batteries could become commercially viable – namely, efficiency, usability and cost.

The original prototypes were too heavy and could not maintain or deliver a strong-enough power output to be worth the expense.

It was Japanese electronics giant Sony that introduced the world’s first lithium-ion rechargeable battery in 1991 and leveraging its technical superiority to propel their camcorder product range.

Within four years, camcorders had created the biggest source of demand for lithium-ion batteries.

By the turn of the millennium, laptops had become the biggest driver of demand and just five years after that, it was mobile phones that were swallowing up the most lithium-ion batteries.

Smartphones and electric vehicles are the most lithium-dependent industries with consumer demand primarily responsible for the huge boost in global lithium mining activity.

Less than 10 years ago, not many would have predicted the lithium boom that would occur.

But, now, industry analysts are forecasting the lithium-battery value chain to be worth trillions of dollars in the foreseeable future.