Tin, the often-overlooked member of the base metals complex, is back on analysts’ agenda.

London-based Capital Economics has just issued a client note entitled A minor star called tin.

Reuters has just dubbed it “the most resilient base metal so far this year”, having bounced from US$12,700 per tonne in March when the markets were buffeted by the strongest of the COVID-19 gales to US$17,010/t at the end of last week.

That last figure may sound good, but in March 2011 tin reached US$31,800/t, the price on that one day rising by US$1,200/t.

And many new potential players would be looking for at least a US$20,000/t price to make their projects financially viable.

Roskill, the long-established British metals research firm, pointed out the bottom line: that is, annual refined tin demand is expected to rise by up to 100,000t — that figure equalling about a third of present world production — over the next decade while annual global mine production is expected to rise by only 20,000t.

Tin has come a long way since 25 August 1810, when Peter Durand was granted British patent no 3,372 for coming up with tinplate containers as a means of preserving animal and vegetable food products.

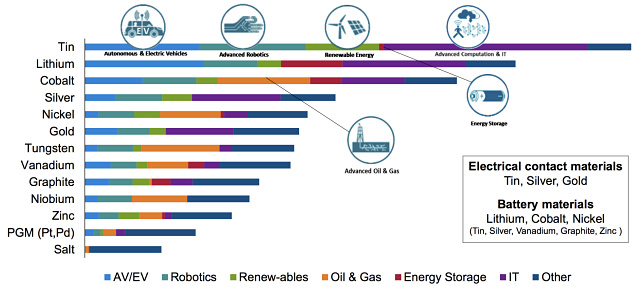

Now many tin explorers include in their presentation a chart put together by Rio Tinto and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology showing that, of all the metals, tin is the one most impacted by new technology — more than lithium, cobalt, silver and graphite.

In recent months, there has been a report from a Chinese university explaining how adding tin can improve solar cell output, and other research showing how the metal can improve performance of lithium-ion batteries and water treatment technologies.

Tinplate linings of cans containing food and drinks (and other uses of tinplate) now account for just 13% of the metal’s consumption.

Solder (in electronics and electrical products, particularly) consumes 48% of tin being produced, followed by chemicals at 17%. Lead acid batteries and copper alloys are also important.

Demand for tin for use as solder may be about to increase just as mine supply tightens further.

Miniaturisation in electronics is slowing while batteries in electric vehicles need tin and that sector is expected to grow substantially over the next decade.

The long, hard road to getting a tin mine into production

Australia has boxed above its weight in the past: during the high tin prices of the mid-1970s to mid-1980s Australia was one of the largest tin-producing countries in the world, yet it has only 3% of the world’s known resources.

In the past two decades, though, getting a tin mine into production has — largely — been a thankless task.

The tone in the early 2000s was set by the experience of the former Marlborough Resources.

In 2001 it shipped the first tin consignment from the revived Ardlethan mine in NSW (which had been in production from 1912 until the 1980s), but by 2004 Marlborough had gone into administration due to financial problems.

Since then, several other companies have quit the sector, and Australia’s tin ranks are now thin.

In 2013, this correspondent wrote that (at that time) there were 70 tin projects around the world which had the potential to go into production, but owners were finding that it could take decades to get from discovery to production.

The International Tin Research Institute in London (ITRI, now the International Tin Association) outlined in a study that that those 70 projects had between them compliant resources of only 1.2Mt of contained metal. Moreover, most of them were at either a very early stage or dormant and most of them were judged as needing at least a decade to get to the development stage.

“On average, it appears it takes 10 to 12 years to progress from the publication of a maiden compliant resource through to initial production,” said ITRI at the time. (And, of course, it takes several years to get even to the maiden resource status.)

“Only a handful of them are likely to become operating mines in the next few years.”

And so it has been proved.

That year, too, the World Bank warned that by 2032 there may not be enough tin to go around to all those making electronic items and needing tin solder for them. That seems to dovetail with the latest Roskill estimates of miners being able to supply only one-fifth of the increased demand for tin in the next 10 years.

(In 2011, ITRI’s markets man predicted that Australia could be the main source of new tin mine production within five years. That didn’t happen.)

And it is not as if there is a comfortable accumulated surplus of stock to fall back on — the tin market has been in deficit since 2014.

One issue is that many of the potential projects at present have a drawback: they are either hobbled by high capital costs of developing an underground mine; or they have open pit plans but the deposits are low grade; or they are in risky jurisdictions.

Australian prospects are limited to a few companies

Metals X (ASX: MLX) is Australia’s largest tin producer and last week revealed plans to expand its Renison mine in Tasmania.

The mine’s life has been extended to 10 years, production increasing from between 8,500t per annum and 9,000tpa in the first two years, to more than 10,000tpa from fiscal 2025. That means about 98,000t of tin concentrate over the 10-year plan.

In addition, existing mineral resources and exploration may allow for the mine to be extended further beyond those 10 years.

Elementos (ASX: ELT) — motto: “Tin for an electric tomorrow” — has two projects.

Oropesa in Spain has had 10 years of intensive work to get it to the economic study stage. That study shows it can be developed as a simple open cut operation and produce 2,440tpa. Elementos claims the project to be the “highest grade, lowest cost” tin project under development.

The company also has its Cleveland tin-copper deposit in Tasmania.

Kasbah Resources (ASX: KAS) owns the Achmmach project in Morocco, which although got to the front-end engineering stage, has been stalled by inadequate tin prices.

Venture Minerals (ASX: VMS) has lately been giving most of its attention to its iron ore and copper-gold properties, but has its Mt Lindsay tin-tungsten deposit in Tasmania with 83,000m of diamond drilling completed and a JORC resource.

Stellar Resources (ASX: SRZ) has Heemskirk, located 15km from the Renison mine. A scoping study has shown the mine would have an 11-year life and the capital outlay a modest $65 million.

Heemskirk was extensively drilled by the former Aberfoyle in the 1980s, the contained tin then estimated at 43,700t.

And then there’s 263,000t of tin contained in the progressing Cinovec lithium-tin project in the Czech Republic owned by European Metals Holdings (ASX: EMH).

Over in Africa, AVZ Minerals (ASX: AVZ) this week called for initial tenders for developing its Manono lithium-tin project in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The company also has preliminary membership of iTSCi, the body that checks that tin being shipped out of the DRC has been mined to international ethical standards. AVZ is also talking to potential tin offtake partners.

China’s tin demand coming back strongly

It seems COVID-19 may have been a positive for tin.

Capital Economics argues that the pandemic has caused an unexpected surge in demand for electronics (computers and their peripherals) “as huge swathes of the global labour force have started to work from home”. China’s exports of computers and related items have soared in the past couple of months.

Meanwhile, China is searching for new supply sources and tin output in Myanmar continues to decline. Producers in Peru have been hit by pandemic quarantines, and tin output there has fallen by 5%.

The world’s largest producer, Indonesia’s Timah, has announced it will restrict tin sales this year to 55,000t, compared with 67,794t in 2019.

But analyst Caroline Bain points out that, while the large Bisie mine in DRC will open this year (at 11,000tpa), most other projects are likely to incur delays (quarantine and/or financing) as a result of the pandemic.

She expects a deficit next year.

“The upshot is that we expect prices to rise gradually over 2020 and 2021 and that tin will outperform many of its base metal peers,” Ms Bain added.