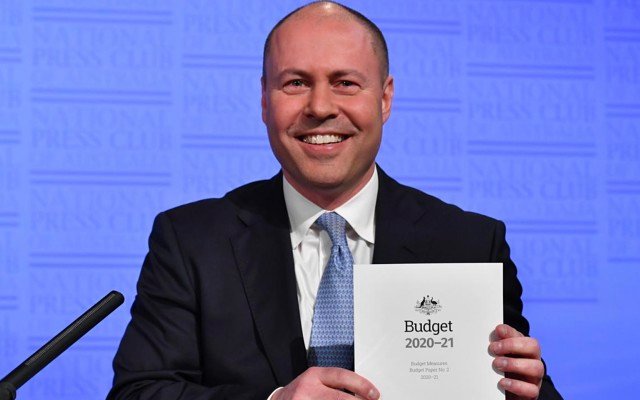

A lot of the analysis of Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s signature Budget has totally missed the point.

Sure, he has made a pronounced and significant shift from his pre-pandemic stance as a fan of balanced Budgets and low to zero government debt.

Now we face at least a decade of Budget deficits and a trillion dollars of government debt that is unlikely to be paid back in our lifetimes after a Budget that incredibly added $128 billion of spending and tax cuts – equal to 6% of GDP – to push the Budget deficit from $85 billion last financial year to $213 billion this year.

That is a massive Keynesian switch by any calculation, even if the Treasurer’s transformation from a debt and deficit opponent still leaves him very uncomfortable using that much criticised Wayne Swan word “stimulus”.

Mr Frydenberg instead opts for “support’’ or similar words where possible but there can be little doubt that this Budget will go down in history as the most stimulatory for a very long time, possibly the most stimulatory forever.

This Budget makes Wayne Swan look thrifty

Surely, by supersizing to the max Wayne Swan’s GFC stimulus spending – which was unfailingly criticised by the Liberal and National Parties, along with the then record Budget Deficit – Treasurer Frydenberg should be forever recognised as the ultimate Australian Keynesian of his time.

After all, he has expanded the Federal Budget’s share of the total economy to an unprecedented 35% of the total economy and produced a projected Budget deficit for 2020-21 almost four times Wayne Swan’s best effort – $214 billion compared to “just” $54 billion deficit back in 2009-10.

Well, not quite so fast.

Switch from welfare to jobs is a vital change

Because Frydenberg committed to a very large and unremarked on switch in this Budget from something famed UK economist and Big Government advocate John Maynard Keynes would have recognised instantly to something he would, perhaps, not have looked on so favourably.

In the initial responses to the extreme economic damage being caused by the pandemic, the Government pulled a very Keynesian lever by increasing income support to the unemployed through the JobSeeker scheme and to the (hopefully) temporarily under-employed through the JobKeeper scheme.

It might seem counter-intuitive for the Federal Government to effectively pick up the payroll bill for large slabs of the economy but that is almost the textbook application of stimulus in response to a sudden recession, which the COVID-19 pandemic and the reactions to halt it caused earlier this year.

When you need to keep money circulating through the economy to preserve as much activity as you can, you give it to people who will spend rather than save it – the unemployed (both existing and new) and the precariously employed, those on the edge of losing their jobs due to the pandemic.

However, an interesting switch came in the 2020-21 Budget with the controversial wind down of both JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments.

In their place were measures strongly focussed on jobs rather than direct economic stimulus – a bring forward of the tax cuts at a cost of $12 billion this year and a thumping $32 billion next year and two youth employment schemes.

There is a $1.2 billion wage subsidy to help Australian businesses hire 100,000 new apprentices and trainees and the JobMaker hiring credit, which will pay businesses up to $200 a week to hire young Australians as part of a $4 billion budget measure to help to bring down youth unemployment during the recession.

So instead of collecting what will soon revert to “the dole’’ – a much lower form of JobSeeker that does not offer much of a living wage – the young unemployed will instead hopefully be swept up by businesses which have been offered wage subsidies and offered jobs.

Creating 550,000 jobs will make a big difference

An impressive 450,000 new jobs under JobMaker and a further 100,000 jobs for apprentices and trainees, if things go to plan.

So why would the Government be trying to get so many people – particularly younger people – back at work by using the stick, in the form of lower dole payments, and the carrot, in the form of subsidised wages and lower taxes?

For all of the usual reasons about looking after the best interests of citizens, of course, because those who stay unemployed due to a recession can be without a job for a very long time.

Jobs help the Budget position in the long term

However, the Government also pulled the switch to jobs for the same reason that our banks spend so much money trying to sign up school students to accounts – it is in their best long-term interests.

Because when you get a young person a job you are also creating a taxpayer that in the long term will provide an excellent form of annuity income for the Government in the form of taxes.

In Keynesian stimulus terms you would have been much better advised to keep paying the enlarged dole in the form of JobSeeker to the unemployed because they would then plough that money straight back into the economy.

They really don’t have a choice because just by surviving they are spending almost all of their welfare payments.

Workers have more choice about spending or saving their money

If those same people are working, they may decide to put any extra money into savings for a future home, investment or holiday rather than spending everything today.

It is a risk but in the longer term, there is little doubt that increasing the pool of wage earners will be better for the Budget bottom line, both in terms of the taxes being paid and also because of the welfare payments that are no longer being paid.

Not to mention the positive economic effects on the businesses involved of having extra workers and all of the consumer spending those workers will do.

Spending is for the short term

The other positive Budget consequence of subsidising jobs is that the program won’t be permanent, so it compares favourably to adding to the stock of public servants by creating new government programs or departments.

Even the tax cuts will eventually wear off in the long term as workers’ wages eventually send them back up the income tax scales through the dreaded effects of bracket creep and fiscal drag.

In some ways the tax cuts are merely handing back some of the previous extra cash milked out by not having the tax scales indexed to inflation.

So rather than being crowned the ultimate Keynesian disciple, Treasurer Frydenberg is perhaps better described as a temporary Keynesian – someone who was not afraid to hit the big spending button in the midst of an emergency but then changed the nature of that spending so that the stimulus would evolve into bolstering the long-term Budget position.

Make no mistake, this Budget was still a massive stimulus document and that stimulus is locked in for the foreseeable future in the form of continuing, albeit smaller, deficits.

It is also potentially optimistic given that it relies on a series of good results including the widespread and effective use of a COVID-19 vaccine.

However, as the spending programs wind down and hopefully the economy and employment resume a growth path, Treasurer Frydenberg has at least given himself or more likely some of his successors, a fighting chance of one day repairing the Budget position.