China’s growing commodity supremacy is being met with resistance by the US courtesy of Australia, after the US Department of Defense (DoD) revealed it was in talks with Australian officials about hosting a rare earth processing facility.

During a press conference on Monday this week, a Pentagon official answered questions regarding the broad span of US foreign policy, including the likelihood of partnering with countries such as Australia and Canada given the close political ties the countries share.

However, despite a clear sign that US authorities are keen to diversify courtesy of Australian production, it was unclear whether the DoD is in talks with public or private entities.

The move is part of a strategic initiative to reduce the existing reliance on China for a variety of rare earth minerals, used to manufacture military equipment and highly specialised devices.

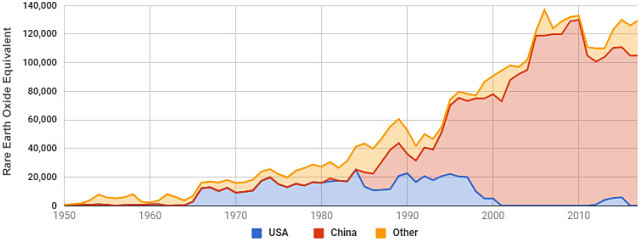

As things stand, China ranks as the world’s largest rare earth producer accounting for more than 80% of global production and processing capacity.

Meanwhile, the US is lagging far behind with just one operational rare earth mine and not a single processing facility despite the country being the runaway leader in the production of arms and military equipment.

In addition to defence sector applications, the manufacture of consumer goods is also in the spotlight given their comparable reliance on rare earth minerals.

There is a multitude of rare earth elements, with 17 specific varieties playing a vital role in consumer electronics including Apple AirPods and iPhones, green technologies such as General Electric wind turbines and Tesla electric cars, as well as medical tools like scanning equipment.

The major rare earth minerals in question are yttrium, lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, promethium, samarium, europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, lutetium and scandium.

The only US processing facility that is due to come online in the foreseeable future is California’s Mountain Pass mine, which is currently building a plant that is expected to begin operating sometime in 2020.

The mine’s previous owner, Molycorp, spent over US$1.5 billion (A$2.22 billion) building a separation facility for producing rare earth concentrates.

Regrettably, as far as the US Government is concerned, Molycorp did not complete a downstream processing unit needed to produce purified rare earth materials before the company went bankrupt in 2015, as a result of intense competition – namely from Chinese producers who are able to operate such facilities at far lower cost than their US counterparts.

The mine’s new owner, MP Materials, plans to complete and reactivate the mothballed facility next year with feasibility studies indicating the mine could turn a profit this time.

From geopolitics to economics

From a geopolitical perspective, the status quo means that China is a commodity monopolist, and therefore, threatens US hegemony on the world stage – especially when it comes to maintaining the security of production and improving industrial self-sufficiency.

In a thorough annual report costing US$181,000 (A$268,000) to the US Congress by the DoD, the agency said that China’s leaders are “leveraging China’s growing economic, diplomatic, and military clout to establish regional pre-eminence and expand the country’s international influence”.

The report cited mega-projects such as China’s “One Belt, One Road” Initiative (OBOR) which the authors said would “probably drive military overseas basing through a perceived need to provide security”.

Another risk factor that has pushed the US into closer ties with Australia, as a means of diversifying its commodity supply lines, is the recent downturn in trade relations between the US and China.

As a result of political rhetoric, in addition to a rise of “America first” inwardly focused policies initiated by President Donald Trump’s administration, the US and China are currently embroiled in a tit-for-tat trade war.

In recent months, both nations have hiked tariffs, imposed quotas and import duties on a variety of goods traded between the two countries.

In June this year, China more than doubled import duty on concentrates to 25% and has also levied tariffs on US$110 billion (A$163 billion) of US products. In retaliation (or as China claims, due to growing “unilateralism and protectionism”), the US imposed tariffs worth US$250 billion (A$370 billion) on Chinese goods.

During 2018, US policymakers enacted three rounds of tariffs, placing duties of up to 25% on a range of Chinese products – from handbags to railway equipment.

In response, China’s State Council led by Xi Jinping hit back with tariffs ranging from 5% to 25% on US goods including chemicals, coal and medical parts.

Even before he became US President in 2016, Trump has been a vocal critic of China’s actions on the world stage, claiming that the country is enacting unfair trading practices and turning a blind eye to intellectual property theft.

Meanwhile, China claims that the US is attempting to curb the country’s legitimate right to rapid growth and development, in fear of the most frenzied economic competition since the Cold War when the US and Soviet Union vied for global supremacy in geopolitical and economic respects.

Last month, Trump ordered the Pentagon to seek out alternative sources of magnets made from rare earths and warned that the nation’s defence infrastructure would suffer without adequate stockpiles.

“We’re concerned about any fragility in the supply chain and especially where an adversary controls the supply,” said Ellen Lord, the Pentagon’s undersecretary of defence for acquisition and sustainment.

“The Pentagon is looking at several options to partner on rare earth processing facilities – one of the highest potential avenues is to work with Australia,” she said.

According to Reuters, a separate spokesperson authorised to speak on the matter said that “continuity and guarantee of supply of rare earths and critical minerals are vital to a range of sectors, including defence. Cooperation with international partners is integral to this effort.”

Australian market impact

According to market analysts, Australian miner Lynas (ASX: LYC) is central to the Pentagon’s proposed plan to diversify its reliance on rare earths.

The firm operates a mine in Australia in tandem with a processing plant in Malaysia but doesn’t have the capability to handle heavy earth separation processes required for the materials needed by the DoD.

In related news, Lynas was the subject of a potential takeover since March 2019 by Australian conglomerate Wesfarmers (ASX: WES).

The company proposed to acquire Lynas for $2.25 per share, although the proposal was scrapped earlier this week, in part due to Lynas electing to renew the operating licence for its LAMP facility in Malaysia.

As a condition of the renewal, Lynas agreed to relocate its cracking and leaching activity (the first stage of its operations currently located in Malaysia) to Western Australia as part of its overarching “Lynas 2025 growth plan”.