Tanzania, currently Africa’s fourth largest gold producer, could be following in the footsteps of the continent’s other nations in restricting foreign involvement in its mining sector following the appointment of Idris Kikula as chairman of the country’s newly-formed mining commission.

The formation of the commission follows months of discussions between Tanzanian authorities and the country’s largest gold miner, UK-listed Acacia Mining (LSE: ACA) which operates three major mines in the country including Buzwagi, North Mara and Bulyanhulu.

Acacia operates under parent company Barrick Gold (NYSE|TSX: ABX), currently, the largest gold miner in the world producing a mammoth 5.52 million ounces of gold per year.

To the displeasure of foreign investors, Tanzania passed fresh mining laws last year in an attempt to decentralise decision-making from the mining minister and increase government revenues by placing a 1% inspection fee on the value of mineral exports and legislatively guaranteeing a minimum state-ownership stake of 16% for all resources projects.

Also, Tanzania sought overarching powers to dissolve contracts, block international arbitration and ban unrefined exports.

Politically-inspired economic wrangling

The reason for the hullaballoo in its resources market was tax related — in the same vein as other countries on the continent including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Zambia, Mali and Namibia and South Africa in recent years.

Tanzania accused Acacia of massive tax evasion in 2016, which triggered a still-ongoing case that slapped a US$190 billion tax bill on the mining major.

However, Acacia has always denied any wrongdoing and remains adamant it has paid all of its legally-required taxes as stipulated by Tanzanian law to-date. Acacia said it was “seeking an adjudicator” to resolve its dispute with the Tanzanian Government and said its operations were not under any threat from the new commission.

Despite the news and the uncertainty over taxes and royalties, Acacia’s shares were up 12% in trade on the LSE, while Barrick Gold was up 2.5% in trade on the TSX when the news first hit the news wires.

However, by the end of trading 19 April Acacia shares were down 13%, indicating that uncertainty is dominating investor sentiment with regards to whether the gold miner can come out of this debacle unscathed.

The company’s shares are expected to gyrate with many investors stepping back from the gold miner in light of Tanzania’s new mining commission, as well as, ongoing export ban which weighed on the company’s first quarter earnings this week.

Permitting changes

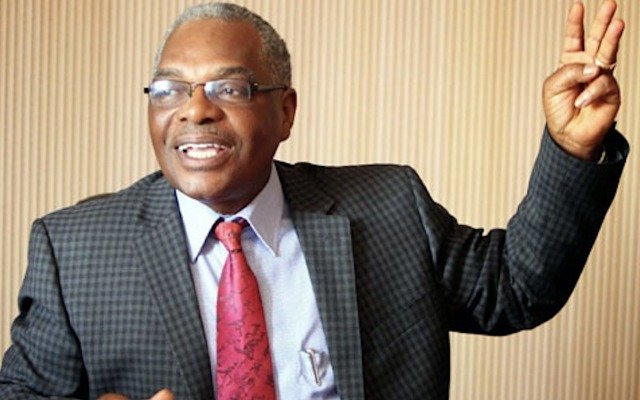

The mining commission’s new chairman Mr Kikula was previously vice chancellor of a state university and has eight commissioners serving under him.

The series of appointments are likely to mean the issuance of new mining licences with potentially different terms for foreign miners operating in the country. Importantly, for foreign explorers and miners, Tanzanian authorities said that the new appointments “would take effect immediately”.

The legislation which created the commission says one of its key objectives is “to advise the government on all matters relating to the administration of the mineral sector with a prime focus on monitoring and auditing of mining operations to maximise government revenue.”

Much like in the DRC, Tanzania’s newly-formed commission has also been tasked with “curbing smuggling of minerals and tax evasion by mining companies” and has powers to suspend and revoke mining exploration and exploitation licences and permits.

As part of a radical shift in permitting power, the commission will also be responsible for “monitoring and auditing both the quality and quantity of minerals produced” — and crucially for miners of all sizes — which raw commodities are able to be exported by large, medium and small-scale miners to determine their tax liabilities.

Furthermore, the commission will be required to “audit capital allocation” being conducted by large miners including the sortation and assessment of minerals produced for tax purposes.

Another potentially prohibitive measure is the commission’s ability to set “indicative prices” of minerals with reference to local and international markets for the “purpose of assessment and valuation of minerals and assessment of royalties”.

Risks and rewards

According to mining analysts, Africa’s fourth-largest gold producer is seeking a bigger slice of the pie from its vast mineral resources by overhauling the fiscal and regulatory regime of its mining sector.

Tanzanian President John Magufuli has already ruffled feathers among miners in Tanzania by enacting a series of measures since his own appointment in 2015 — measures which he says are “aimed at distributing revenue to the Tanzanian people”.

In other words, measures that extract greater commercial value from existing mining operations and provide greater flexibility for Tanzanian authorities to monetise its natural resources wealth.

Such issues are becoming more common across sub-Saharan African nations in recent years amidst the ever-present tussle between voter-pleasing domestic governments and commercially-savvy foreign resources companies.

In July last year, President Magufuli suspended the issuance of all new mining licences until the new mining commission was in place.

With the imposition of a new mining commission and Acacia’s tax evasion case still far from resolved, it seems investors have not been flustered by the news.

Much remains uncertain in Tanzania (and Africa) although its rich resource-laden geology is still expected to produce the lion’s share of raw materials to be sold on world markets.