Crude oil prices have been rising in recent times with continued geopolitical uncertainty the main culprit to blame.

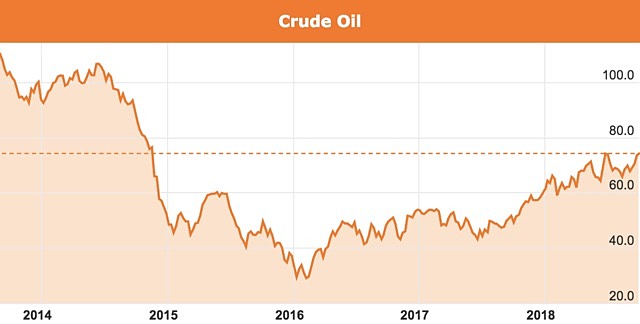

Both WTI and Brent crude prices reached 4-year highs this week despite an 8-million-barrel increase in US stockpiles and set against a backdrop of continually stronger US oil production over the past decade, otherwise known as the ‘shale boom’.

WTI crude hit a high of US$75.30 per barrel on the New York Mercantile Exchange, while Brent, which tends to trade with a market premium to WTI, hit a high of US$84.98pb on the London-based ICE Futures Europe exchange.

With prices peaking again, there have been mixed responses from market analysts and oil-stock investors.

Some contend that prices are headed back above $100pb while others see the latest oil price spike as a temporary blip on an otherwise downwards oil price trajectory that remains weak due to flat global demand and continued transition into renewable clean energy – possibly the oil industry’s biggest existential threat.

Iran sanctions

One of the reasons that explain the recent highs, as cited by market analysts has been the ongoing saga in the Middle East, and more specifically, Iran.

US President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw his country from the Iran nuclear deal in May this year has reignited renewed geopolitical uncertainty given Iran’s dominant position in the oil production stakes.

Iran is currently OPEC’s third-largest producer pumping out around 2 million barrels per day – a figure the US is desperately trying to change by applying political pressure, sanctions and encouraging buyers to turn to alternative sources of oil.

According to several sources including US policymakers, the US wants to see Iran’s oil export fall to zero with a key deadline of 4 November for buyers to switch away from Iran, now looming large on the horizon.

According to the Institute of International Finance, overall exports from Iran have dropped to 2 million barrels per day (bpd) in September from 2.8 million bpd in April, with further declines now seeming ever more likely.

To replace the output generated by Iran and to maintain stable prices, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Venezuela are vying to sell more of their output in global markets.

However, the geopolitical game of cat and mouse extends to Russia and Venezuela just as much as it does with Iran.

Geopolitical instability

Russia is currently under sanctions for a raft of alleged political machinations while Venezuela is gradually sliding into self-inflicted civil war on the back of internal political conflict presided over by embattled president Nicolás Maduro.

Just like Russia and Iran, Venezuela has also had sanctions imposed on its exports including oil, as a response to its crackdown on Maduro’s political opponents, journalists and establishment critics.

So, with three of the world’s top oil producers facing various kinds of strife, it’s not a huge surprise to see oil prices trending higher towards record highs.

Quite coincidentally, the US wants to step in and alleviate oil price volatility with its own production which has doubled in the past decade.

Oil price inflation

US oil producers have expanded production from around 5 to a record 11 million barrels since 2007.

The sharp production increase, to a large extent boosted by unconventional exploration methods, has coincided with WTI crude prices falling as low as $30pb in 2016.

However, the past four years have welcomed increasingly more oilers into production as prices have again trended higher, now trading at around US$76 per barrel.

To underline its newly-found oil market dominance, the US became the world’s largest producer of crude oil earlier this year – for the first time since 1973.

Looking deeper, it has been the state of Texas that has been at the centre of the shale boom.

Production in the Permian Basin of West Texas has grown so quickly that in February the United States vaulted above Saudi Arabia for the first time in more than two decades, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

The case for falling prices

As with any resource or commodity, markets tend to follow cycles.

Periods of low demand lead to falling production as oilers cut back spending on new projects. As demand rises, production tends to rise as an adjustment mechanism as oilers see better returns from higher prices.

In 2015, the excess of production over consumption was as much as 3 million barrels a day according to the International Energy Agency.

Fast forward to today and droves of market analysts are calling for OPEC countries to raise production by as much as 1 million barrels a day in order to alleviate Iran’s forecast export drop in the coming months. The effect can also be seen amongst oil companies themselves.

Executives at the world’s biggest oil and gas companies are discovering that rising oil prices have made a strong case to loosen the purse strings to replenish reserves, halt output declines and take advantage of a crude price rally after years of range-bound prices.

With oil at four-year highs, the same oilers that were cutting back production merely three years ago, are now back out in the field looking for additional reserves and hiring more staff across the board.

According to market research published by Morgan Stanley, spending by the world’s top seven oil companies is expected to rise to a combined US$136 billion by 2020 from US$105 billion in 2017.

“New project awards will likely already accelerate in 2019, but for major developments, capex in the first year tends to be limited. From 2020 onwards, capex is likely to go higher,” the investment bank said in the research note this week.

Ratings agency Moody’s has also said that higher oil prices were helping oil majors to record more substantial profits and these profits, in turn, were spurring a more upbeat attitude towards higher expenditure.

Reuter’s oil market analyst John Kemp says it best: “The oil industry has been characterised by deep and prolonged boom-bust cycles since the first modern well was drilled in 1859. Deep cycles are the natural condition of the oil industry and there is no reason to think the future will be any different.”