Controversial agrochemical giant Monsanto has made history this week for all the wrong reasons.

On Tuesday, the company was ordered to cough up $2.96 billion in damages to an elderly US couple who claimed long-term exposure to the glyphosate ingredient in its weed killer Roundup caused them to both contract non-Hodgkins lymphoma within four years of each other.

The 17-day trial was the third defeat against the corporation which has fast become one of the most hated in the world, not just for its high-risk herbicide but also for its patented, genetically-modified seeds which have been bred to be glyphosate-resistant.

During the proceedings, jurors discovered that Monsanto had engaged in “reprehensible conduct” by burying industry studies which found its products were harmful and instead, fabricated new papers promoting safety.

Prosecutors submitted excerpts of internal Monsanto emails which talked of ghostwriting scientific papers and covertly paying front groups such as the American Council on Science and Health to publicly promote glyphosate as a safe option.

Other documents shown during the trial illustrated close ties to officials within the US Environmental Protection Agency who were presumably led into backing the safety of Roundup, and strategies to discredit international cancer scientists who had previously classified glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen”.

Record payout

Tuesday’s mammoth payout – which includes more than $79 million in compensatory damages and $2.89 billion in punitive damages – is believed to be the largest jury award in the US so far this year and the eighth largest payout in a product default case ever.

It follows several recent legal battles that Monsanto has faced concerning Roundup, with an estimated 13,000 new cases launched at US state and federal level.

The vast majority of these lawsuits focus on the same claim – that Roundup’s key ingredient poses a serious health risk to users and could well be linked to cancer, despite Monsanto and its parent company Bayer AG flaunting the exact opposite.

“Glyphosate-based Roundup products have been used safely and successfully for over four decades worldwide and are a valuable tool to help farmers deliver crops to markets and practice sustainable farming by reducing soil tillage, soil erosion and carbon emissions,” Bayer said in a statement following the landmark legal win.

“Regulatory authorities around the world consider glyphosate-based herbicides safe when used as directed … the consensus is that [they] can be used safely and that glyphosate is not carcinogenic.”

Bayer said it was disappointed with the jury’s decision and would lodge an appeal.

Mixed findings

First registered in the US in 1974, glyphosate has become the most widely-used herbicide on the planet, with reports suggesting more than 9 million tonnes have been sprayed on fields worldwide in the last 45 years.

In March 2015, the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer – comprised of 17 experts from 11 countries – identified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans”, prompting a flurry of mixed findings from other health agencies.

The EPA (with its aforementioned Monsanto connections) weighed in on the new debate in late 2015, finding that glyphosate was “not likely” to cause cancer or pose any other meaningful risks to human health when used according to instructions.

A subsequent review by the European Food Safety Authority concluded it is “unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans and the evidence does not support classification with regard to its carcinogenic potential”.

In 2016, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority conducted its own investigation, finding that “based on current risk assessments, the label instructions on all glyphosate products – when followed – provide adequate protection for users”.

Cancer risk is real

In stark contrast, researchers from the University of Washington evaluated existing studies into the chemical earlier this year and found that long-term use of glyphosate can actually raise a person’s risk of developing cancer by as much as 41%.

Their analysis focused on data relating to people with the highest exposure to the chemical and found “a compelling link between exposure to glyphosate-based products and an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma”.

In a statement at the time, Bayer called the analysis a “statistical manipulation” with “serious methodological flaws”.

“This paper provides no scientifically-valid evidence that contradicts the conclusions of the extensive body of science demonstrating that glyphosate-based herbicides are not carcinogenic,” it said.

Monsanto’s reaction

Widespread debate on the safety of glyphosate triggered the first major lobbying by Monsanto and a raft of multi-million dollar lawsuits from people who believed exposure to the chemical had caused their cancer.

In 2018, rumours surfaced that Monsanto had spent millions of dollars on covert public relations campaigns to finance articles discrediting independent scientists who established links between the herbicides and the human immune system.

Other reports highlighted the company’s continued links with EPA officials who have repeatedly backed assertions about the safety of its glyphosate products.

Interestingly, Monsanto’s employee safety recommendations require the wearing of full protective gear when applying glyphosate herbicides, however the company has never officially warned the public to do the same.

This oversight worked to the company’s detriment in August 2018, when it was hammered by the first of many Roundup lawsuits to the tune of $417 million on the basis that it had failed to provide sufficient warning of potential health hazards, including cancer, on the product’s label.

The jury found Monsanto had acted with “malice and oppression” because it knew what it was doing and it did so with “reckless disregard for human life”.

After the trial, Monsanto vice president Scott Partridge rejected any link between glyphosate and cancer, insisting the “verdict doesn’t change the four-plus decades of safe use and science behind the product”.

Glyphosate ban

Two months ago, Vietnam announced it would ban the importation of glyphosate-based herbicides with immediate effect after Monsanto was ordered to pay $115 million in damages to the plaintiff of a second cancer-related lawsuit.

In April, the country’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development removed the chemical from the national list of authorised products.

Both moves will likely have a ripple effect on the bottom line of Bayer’s Asian business.

Chemical use is a controversial subject in the South East Asian nation, which harbours painful memories of the damage caused by dioxin-based product Agent Orange during the Vietnam War.

Monsanto was one of a handful of companies which produced Agent Orange and its main poison, dioxin.

While the original aim was to use the chemical to destroy vegetation in rural areas occupied by the Viet Cong, the toxic concentrations were found to be up to 13 times higher than those usually used in agriculture and other non-military fields, and disastrous results ensued.

Generations later, more than three million Vietnamese are believed to still be affected by the 20 million gallons of Agent Orange sprayed by the US military over Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in the 10 years to 1971.

The event has been linked to serious health issues including cancers, severe psychological and neurological problems and birth defects among Vietnamese people and former US military personnel.

The end of Monsanto?

Bayer’s US$63 billion acquisition of Monsanto last year created the world’s largest seed and agrochemical company, uniting the former’s pesticide business with the latter’s genetically-modified crop portfolio.

At the time of the proposed deal, Bayer announced plans to phase out the 117-year old Monsanto brand name as part of a wider campaign to win back consumer trust.

Acquired products would retain their brand names and become part of the Bayer portfolio.

Bayer’s crop science division president Liam Condon said consumer engagement would be key to regaining the public’s confidence.

“The important point, once we change the company name, is that we talk about what the new company will stand for,” he said.

“Just changing the name doesn’t do much — we’ve got to explain to farmers and ultimately to consumers why this new company is important for farming, for agriculture and for food, and how that impacts consumers and the environment.”

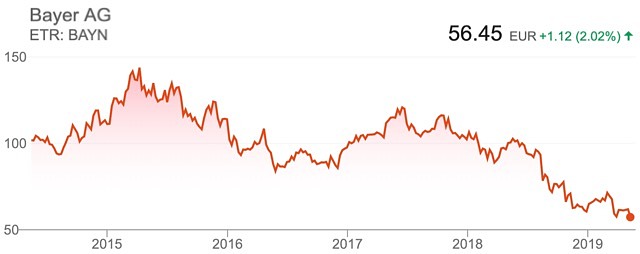

Bayer’s share price has plunged 40% since the acquisition, largely in response to courtroom dramas which prior to the recent ruling have already totalled over $230 million in damages.