Unlike gold where you can get a firm idea of a project’s value from grade and width, other minerals like vanadium can be harder to assess.

Vanadium expert and Australian Vanadium (ASX:AVL) technical manager Todd Richardson told Small Caps that when it comes to evaluating a vanadium deposit, much more than grade comes into play including the proposed processing route and the amount and type of minerals present.

“With gold, you can look at different deposits and have an idea of the value from the grade, because the processes are all the same,” Mr Richardson said.

“You know exactly how much it is going to cost to process this gold.”

“Vanadium is totally different. It’s almost the other way around,” he explained.

Several advanced vanadium explorers have created their own proprietary processing technology including TNG (ASX: TNG) with its TIVAN technology, which the company anticipates will produce titanium dioxide, vanadium and iron products.

Another vanadium explorer King River Copper (ASX: KRC) is looking at using sulphuric acid or heap leaching to extract similar vanadium, titanium dioxide and iron oxide materials.

Although these new technologies are yet to be proven as commercially viable, Mr Richardson pointed out that he had no doubt new technology will play a role in advancing the vanadium scene.

Traditional vanadium processing

Currently, the world’s largest primary vanadium producers include TSX-listed Largo, AIM-listed Bushveld Minerals and LSE-listed Glencore.

These companies have operations in Brazil (Largo) and South Africa (Bushveld and Glencore) and all use the same commercially proven processing method, which involves salt roasting and water leaching.

Largo operates the Maracas Menchen vanadium mine which is predicted to produce up to 10,150 tonnes of vanadium during 2018.

Meanwhile Bushveld has three assets in in Africa, and the company’s Vametco mine is expected to generate about 3,750tpa after recently reaching nameplate capacity.

Adding to the vanadium scene is Switzerland-based Glencore’s Rhovan operation, which creates ferrovanadium and vanadium pentoxide for world markets.

Back in Australia, one of the few vanadium explorers looking at using the commercially proven traditional salt roast, water leach technique is Australian Vanadium at its flagship Gabanintha project in WA.

With a complete pre-feasibility study due out shortly, Australian Vanadium’s metallurgical testwork on Gabanintha ore has found it amenable to the same processing route used by these major producers.

Geology

Feeding into a vanadium project’s planned processing method is the deposit’s geology.

Vanadium is a by-product of numerous minerals including oil shale, uranium and graphite. However, liberating vanadium from these deposits can often be uneconomic due to the amount and type of additional treatment required.

Mr Richardson pointed out that existing primary vanadium production arises from magnetite deposits.

When looking at a magnetite-style vanadium deposits, the key component within all the ore is the magnetite.

He explained that vanadium miners are only interested in the magnetite, with the remaining ore eradicated as waste.

“Then, once you get rid of that waste, and you have the concentrate, there’s also a question of how much vanadium is actually in that magnetite that you’ve concentrated.”

“And that varies from deposit to deposit.”

Mr Richardson pointed out deposits in South Africa’s Bushveld Complex often comprised 30% magnetite, with the remaining 70% of ore deemed waste.

“That 30% of ore that contains magnetite grades averaging somewhere around 1.8% to as high as 2.2% vanadium pentoxide.”

One ASX-listed vanadium explorer Tando Resources (ASX: TNO) is currently firming up a high-grade vanadium operation within the Bushveld Complex, with Tando saying the project is in a similar geological setting as Glencore and Bushveld’s operations.

Typical of the region’s geology, Tando has reported numerous high-grade results from ongoing exploration at the project.

A different perspective

When looking at Australian Vanadium’s Gabanintha deposit, Mr Richardson noted that although the ore was a lower grade than Bushveld, there was much more magnetite.

“So, instead of discarding 70% of what we will mine, we will discard only about 40%.”

“Now, the magnetite we have left is lower grade than the magnetite you have in the Bushveld Complex, but it is still a fairly high-grade magnetite concentrate at about 1.35% to about 1.4% vanadium pentoxide.”

So, when looking at magnetite vanadium deposits, there are two primary factors to consider: how much actual magnetite is in the ore; and, then, how much vanadium is present in that magnetite.

“Often, reports just give you the grade, for example: 0.4% vanadium pentoxide in the ore. However, this number doesn’t really tell you anything because you don’t know how much vanadium is in the magnetite.”

“There can be a substantial amount of vanadium that’s not in the magnetite and if it is in the waste product, then you can’t hope to concentrate it. You’re just going to be throwing that vanadium away.”

“That’s why it always helps when companies tell you both the vanadium grade and magnetic concentrate and then the expected mass recovery from the ore.”

Mr Richardson added that these figures can’t really be known with a high degree of confidence until a pre-feasibility study has been completed.

Vanadium market dynamics

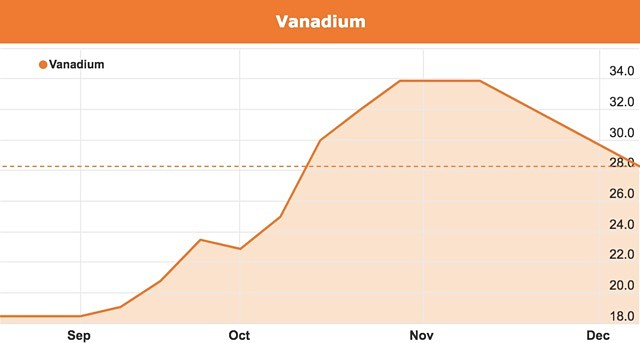

The vanadium market is booming with the commodity’s price up more than 840% in two years – almost reaching US$35 per pound for 98% vanadium pentoxide in November.

Although, currently down marginally to US$28/lb, the vanadium price is a far cry from lows of US$3.50/lb at the start of 2017.

Driving the demand is a strengthening steel sector and the rapidly emerging vanadium redox flow battery.

The rapid vanadium growth is anticipated to continue in the near-term – driven by China’s new steel rebar standards, which require more vanadium.

Australian Vanadium’s managing director Vincent Algar told Small Caps that analyst consensus is that this current price is not a spike, but, rather, a result of a “step change” in the market.

“This is a slow and steady increase from an all-time low where we had a supply shock to the market,” Mr Algar explained.

Now, the vanadium market will feel added pressure as steel production, which accounts for 90% of vanadium consumption, will begin competing with the growing vanadium battery market, which is expected to swallow up 20% of vanadium production by 2030 – up from its current market share of 2%.

However, Mr Algar noted that despite the tight market dynamics, the vanadium price will come down eventually, knocking out the high-cost vanadium producers.