With gold prices at all-time highs and as the precious metal gears up for what many analysts are calling a decade-long bull run, it’s an opportune time to look at the numerous ASX gold stocks looking to lock-in a slice of the pie.

In June this year, the precious metal’s price exceeded A$2,000 per ounce for the first time and is now trading at all-time highs.

Economist and author Jim Rickards said we are in the fourth year of the current bull market, which started off slow because of “bad sentiment”.

Mr Rickards said he expects the current gold price momentum will pick up, claiming it’s not too late to get on the train, with the next leg of the bull market about to unfold and tipped to hit as much as US$10,000/oz or A$10,000/oz over the next 10 years.

Underpinning the metal’s rising price are increased buying from central banks, higher gold-backed Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) holdings, and growing jewellery purchases in India.

The rise in central bank buying and ETF holdings is being driven by several factors including weakening global economic fundamentals such as low and negative interest rates, resulting in minimal yields.

Low inflation and political uncertainty in major regions are also large factors, including the ongoing trade war between US President Donald Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping.

The anticipated effects of Brexit have also boosted gold buying in the UK.

Previous gold bull market

Gold’s previous bull market roughly started in 2000 when the metal was hovering at around US$250/oz and continued through to 2011 when it peaked at US$1,923/oz before falling away.

Commenting on what spurred the previous bull run, Martin Place Securities executive chairman Barry Dawes told Small Caps the period between 1987 and 2002 was the “equivalent of the 1930s Depression for the commodities sector”.

Gold hit is low of US$246/oz in 1999 and this was retested in 2000.

Global events at the time included China’s emergence on the world stage, combined with loose monetary conditions, the horrific 9/11 air crashes and US’ invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Commodity prices then began to rise led by oil, copper and gold.

By 2007, inflationary pressures were mounting in the US, and the situation was exacerbated by the US housing bubble, which strained the country’s banking system.

“Global debt levels were also causing great concern,” Mr Dawes said.

“Gold started running as inflation, fear and a weaker US dollar were developing.”

He added interest rates began to decline around the world and overstretched US banks like Lehman Bros and other financial corporations collapsed as the US housing bubble burst triggering the global financial crisis.

Gold continued higher – hitting US$1,032/oz in March 2008, but was then dragged down with the rest of the commodity markets as the GFC unfolded.

However, as the US Federal Reserve began to bail out struggling institutions between 2009 and 2011, gold again became a safe haven – running up to US$1,923/oz by September 2011, before beginning a “massive decline” over the following four years.

What is different now?

According to Mr Dawes, this current bull run is “very different”.

“The rise of China and India and the continuing strong demand for gold by their citizens has, in my view, transferred and removed all the tradeable gold from the West over to the East,” he explained.

“The availability of gold is now very restricted and short positions still need to be covered.”

He added the global debt position has also risen and the effect of negative interest rates are yet to be fully understood.

With the US dollar remaining firm, Mr Dawes said the true supply and demand issues for gold were now dominating.

“Gold is slowly re-establishing its position as part of the global monetary and currency system.”

“Central banks are buying up gold to further tighten the market,” he added, pointing out that gold prices are now rising in all currencies, with the precious metal commanding all time highs in most currencies.

The gold run this time round is also very different for Australian miners, because the Australian dollar was above parity at the previous 2011 peak.

That meant in Australian dollar terms gold fetched a lower price compared to the US dollar gold price, which is vastly different to the current situation, with gold trading around A$2,102/oz and US$1,432.28.

Australian gold exporters are now locking-in prices for the precious metal they’ve never before seen.

Where is the gold price heading?

Mr Dawes explained that with the current supply and demand fundamentals, gold has the potential to run to “very high prices”.

“Gold is now well over A$2,000/oz and is at or near all-time highs.”

He said he anticipated the US dollar gold price to exceed US$1,600/oz by the end of 2019.

With the Australian dollar gold price traditionally higher than the US price, Mr Dawes said he expects the Australian dollar gold price to trade around A$2,220/oz by year-end.

He added that gold was seasonally strong in the December half of the year and attracted its highest prices in December.

Contributing to the environment is a rundown in gold inventories caused by the increased buying – creating a much tighter gold market.

What is gold and what are its main markets?

The soft shiny yellow metal gets its name from the Latin name aurum, which means glow of sunrise or shining dawn.

One of the reasons gold has a long history is it is the most malleable and ductile of all metals, making it easier for ancient civilisations to fashion it into whatever shape or form they desired.

The commodity is also corrosion-resistant and unaffected by air and most reagents. It is a good conductor of heat and electricity and has a melting point of 1,064.18 degrees Celsius.

The metal is believed to be non-toxic and is edible with gourmet shops selling it in the form of glitter, flakes and shapes such as leaves.

Because the metal is fairly unreactive, it requires a mixture of acids to dissolve it.

Gold is part of the “coinage metal” group, which includes other metals that are used to create money such as silver and copper.

Although central banks’ gold buying spree has been much talked about, they only account for a small section of the global gold market.

The metal is primarily consumed in jewellery, with bar and coin demand making up the second largest market for gold.

This is followed by central banks and ETFs, with technology making up a small slice of the metal’s consumption.

In technology, gold is also used as a plated coating on a variety of electrical and mechanical components.

History of gold

Gold’s history in entwined with humankind, with flakes of the precious metal found in Paleolithic caves as far back as 40,000BC.

The first human interactions with the metal can be traced back to ancient Egypt with the Pyramids of Giza capstones built with solid gold.

Egyptians also used gold as a currency and created the first known currency exchange ratio which mandated one piece of gold was equivalent to two pieces of silver.

To procure the mineral, Egyptians developed maps that outlined where the gold mines and deposits were located in the ancient kingdom.

It is believed gold was mined during the Kingdom of Lydia’s (now part of Turkey) King Croesus’ rein in 550BC.

Meanwhile, in ancient Greece, the metal became a symbol of social status. Similar to current times, ancient Greeks viewed gold as sign of wealth. It was also a currency.

Other ancient civilisations used gold, including the Incans and Aztecs in South America, with the metal also referenced in the bible.

Throughout recorded history, the precious metal has been used in jewellery and decorations, as well as eating and drinking vessels and even dentistry.

Across all civilisations, gold has been a status symbol, with those owning more of the precious metal usually in a position of power and wealth.

Even today, gold is a status symbol. In Western culture it represents perfection in the form of gold medals and trophies that are awarded to winners of a competition.

Gold’s history as a currency

With gold used as a currency for thousands of years, it helps to look back at when its use as legal tender began.

Although the metal was initially sourced for status and decoration, its roots as legal tender can be traced as far back as 1500BC when it was traded by ancient Egyptians.

King Croesus of Lydia ordered the first gold coins around 550BC, marking the metal’s first declaration as money.

By 50BC, gold as a currency had infiltrated ancient Rome and Greece and began to spread throughout Europe.

Fast-forward to 1066AD and the British currency system had been established with silver. It is believed the country’s legal tender then expanded to include gold around the 14th Century.

As the 17th Century unfolded, gold production was more prolific and the metal was hoarded and stored in mints.

By 1792, the US adopted the silver-gold monetary system, which set the standard for a dollar to comprise either 24.75 grains of gold or 371.25 grains of silver.

By the late 1800s, most of the world’s currencies had become part of the Gold Standard and were fixed to the metal’s price.

After World War II, the Gold Standard was replaced, and the US dollar became the centre of the world’s currency system due to the country’s political and economic dominance.

It was believed this new system would offer more flexibility than the Gold Standard, which prevented countries from prolifically printing their currencies at whim.

In today’s climate, no modern legal tender system is backed by gold. However central banks still store the metal.

Despite the standard no longer existing, gold is still seen as a safe haven during times of political and economic instability.

This has been evidenced by the increasing amount of central bank purchases around the world, which has tightened the supply chain and triggered the spoken about rises in most currencies.

Global gold production and supply

With such strong gold buying, current production is unable to keep up despite ongoing increases.

Record mine output in the June quarter 2019 rose 2% to 882.6 tonnes, compared to the same period in 2018, while recycled gold leapt 9% in the quarter to 314.6t.

The high gold production follows from a record Q1 2019 and brings total first half 2019 mine production to 1,730.2t – up 1.1% on 1H of 2018.

Higher production was a result of continued ramp up of significant projects across Canada, Russia, and the US, with all three regions posting 9% year-on-year growth for Q2 of 2019.

However, the world’s largest gold producing nation China experienced a 4% decline for the same period, with stricter environmental regulations attributed to the fall.

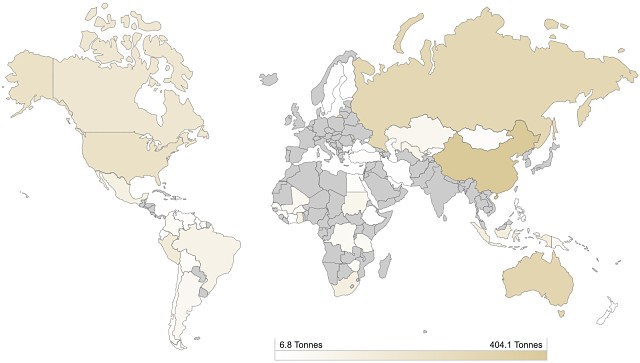

According to the World Gold Council, combined global gold production for 2018 was 3,502.6t – up from 3,442t in 2017.

Behind China and Australia, Russia, the US and Canada were also among the world’s top gold producing countries in 2018.

Demand boosted by record central bank buying

On a global level, gold demand hit 2,181.7t for the 1H 2019 – its highest level in three years.

As mentioned previously, central banks have been buying up gold to diversify from the US dollar and maintain safe liquid assets.

During the first half of 2019, central banks went on a record buying spree scooping up 374.1t for the six-month period, with the June quarter contributing 224.4t – a year-on-year increase of 47%.

According to the World Gold Council, the record buying caused the largest net 1H of 2019 increase in global gold reserves since it started creating its quarterly data series 19 years ago.

According to the council, nine banks added more than a tonne to their reserves during the period.

Leading the buy up was Poland which added an extra 100t to its reserves – growing them by 77%.

National Bank of Poland president Prof Adam Glapinski said the purchase was strategic with the intent of safeguarding the country’s financial security.

The massive purchase bumped Russia back into second place which hoarded an extra 94t during 1H of 2019 – bringing its gold reserves to 2,207t at the end of June.

During the period, China added 74t to its reserves, while Turkey was also a big purchaser scooping up 60.6t, followed by Kazakhstan which increased its reserves by 24.9t in the same period.

Other central banks that added at least a tonne to their gold inventory were India, Ecuador, Colombia and Kyrgyz Republic.

Gold jewellery demand for the June quarter rose 12% to 168.6t – driven by a large number of Indian weddings.

Meanwhile, the US bought its highest amount of gold jewellery in a decade during the first six months of the year – with purchases hitting 53.4t.

Gold-backed ETFs are securities that are physically-backed by gold and account for about one-third of investment gold demand.

ETFs allow investors to own gold without the need for insurance and storage expenses.

“These gold-backed funds seek to combine the flexibility and ease of stock-market trading with the benefits of physical gold ownership,” the World Gold Council explained.

In the June quarter, global gold-backed ETF holdings rose by 67.2t to reach 2,548t with UK-listed ETFs experiencing the largest growth underpinned by Brexit concerns and currency weakness.

Demand for gold-backed ETFs was shored up in the US by the country’s Federal Reserve shifting to a neutral stance on interest rates.

As mentioned previously, investors have been prioritising gold amid low or negative yields, combined with political instability and market volatility world-wide.

Unlocking metal from the ground: gold mining and processing

Generally, gold is sourced from hard rock veins and alluvial deposits and is believed to have originated on earth from meteorites about 4 billion years ago.

Research has also uncovered that earthquakes can create gold.

The metal makes up about 3 parts per billion of the earth’s outer layer and is found in nature in its pure form.

In primary gold deposits, the precious metal is often found with quartz and sulphide minerals like pyrite.

Other deposits such alluvial or placer occur where water flows have caused gold to become concentrated in hollows or trapped in river beds.

It is these alluvial deposits that triggered the Australia gold rushes in the 1850s.

Most of the gold extracted today is found in hard rock deposits and is fine grained.

Within Australia, about 60% of the country’s gold resources are found in Western Australia.

Where there are economic concentrations of the precious metal, it is mined via an open pit or underground operation – sometimes both.

Once the ore has been mined it is then processed which usually involves crushing, followed by treating with chemicals, smelting and further purification.

With free-milling ore, a weak solution of sodium cyanide can be used to leach the gold from other minerals.

About 83% of the gold mined each year is processed with cyanide leach.

Where gold is locked in sulphide minerals, it may need to undergo either roasting or biological leaching.

The material is then smelted and poured into moulds to create gold bullion, which is stacked and transported for sale into domestic and global markets.

World’s largest gold reserves

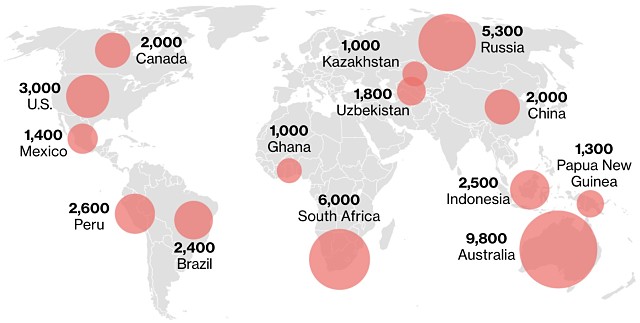

The United States Geological Survey estimates Australia has the largest gold reserves of any other country of 9,800t – equating to about 30 years’ production at current rates, with the country generating 314.9t last year.

Meanwhile, South Africa possesses the world’s second largest gold reserves of around 6,000t.

As South Africa’s mines get deeper, the country’s annual production has declined over the last 50 years from 1,000t in 1970 to almost 130t in 2018.

Despite only owning five years’-worth of reserves (2,000t), China is the world’s largest gold producing nation – generating more than 400t in 2018.

Gold miners that dominate the global sector

Formerly the world’s largest gold miner, Barrick Gold was toppled from its place after Newmont and Goldcorp merged this year to form the world’s largest gold producer.

The newly merged entity will account for 7% of the world’s gold output, with the combined business to generate around 6-8Mozpa for decades.

During 2018, Barrick produced 4.5Moz (attributable), making it the second largest gold producer, while coming in third was AngloGold Ashanti with 3.4Moz, followed by Kinross Gold (2.45Moz) then Freeport McMoRan (2.44Moz).

Newcrest Mining was the only Australian-based miner to make it in the top 10 – skidding in to 7th place with production of 2.41Moz.

Gold Fields which has operations in Australia managed to secure itself a spot in 9th place with its 2018 production of 2.04Moz.

Notable gold deposits and mines across the world

The largest known gold deposit in the world is the Witwatersrand reef in South Africa. Since mining began at the deposit a century ago, it has given up more than 150 billion ounces of gold and is estimated to account for 50% of the world’s gold that has ever been mined.

Over in the US, Newmont and Barrick established the Nevada Gold Mines joint venture on 1 July 2019, with Barrick owning 61.5% and Newmont holding 38.5%.

According to the companies, the joint venture’s combined tier one assets make it the largest global gold producing complex.

In 2018, the combined operations generated 4.1Moz gold – almost double that of the world’s next largest gold mine Muruntau in Uzbekistan.

Navaoi is the current owner of the open pit Muruntau asset which spans 3.35km by 2.5km and purportedly produces more than 2Moz of the precious metal each year.

Based in Indonesia, the Grasberg mine is another gold operation believed to one of the world’s largest – producing 1.1Moz in a year. However, the mine is exploited primarily for its copper at the moment.

Freeport McMoRan sold down its stake in the asset in 2018 to the Indonesian Government which now owns 51% of the operation.

Another gold mine worth noting is Barrick Gold and Newmont’s Pueblo Viejo operation in South America’s Dominican Republic.

The mine is expected to produce up to 600,000oz gold in 2019 and hosts 6.55Moz in proven and probable reserves.

Newmont’s 51%-owned Yanacocha asset in Peru is believed the largest gold mine in South America.

During previous operation, the mine one produced 3.3Moz in a single year, but currently generates 271,000ozpa (attributable to Newmont).

Across the ocean in Russia, Polyus Gold’s Olimpiada gold mine is worth a mention with more than 26Moz in reserves and gold production exceeding 1.3Moz in 2018.

Olimpiada is Polyus’ largest operation and accounts for more than 50% of its total gold output.

Back in Australia, the Boddington and Kalgoorlie Super Pit gold operations are believed the highest producing gold mines in the country.

Newmont’s wholly-owned Boddington mine is 130km south-east of Perth in WA and hosts reserves of 20.3Moz gold with annual output equating to about 700,000oz.

The company also owns 50% of Australia’s other major operation – the renowned Super Pit in Kalgoorlie, which generated 318,000oz for Newmont in 2018 and has total average production of 800,000ozpa.

Barrick holds the other 50% of the mine, which is also Australia’s largest open pit mine and is 1.5km wide.

With assets such as the Super Pit and Boddington, Australia is the world’s second largest gold producing country.

Gold stocks on the ASX

As the gold price continues to rise, it is timely to look at the ASX gold explorers and miners that stand to benefit from the predicted bull run.

Here is the list of ASX listed gold companies:

SEE ALSO:

– Silver stocks on the ASX

– Lithium stocks on the ASX

– Cobalt stocks on the ASX

– Graphite stocks on the ASX

**– Zinc stocks on the ASX

– Nickel stocks on the ASX

– Vanadium stocks on the ASX

– Rare earth stocks on the ASX

– Uranium stocks on the ASX

– High Purity Alumina stocks on the ASX

– Mineral sands stocks on the ASX

– Tin stocks on the ASX

– Tungsten stocks on the ASX

– Hydrogen stocks on the ASX

– Oil and gas stocks on the ASX

– Cannabis stocks on the ASX

**