Gold to face stiff challenges in coming months

The gold bugs must have thought they had died and gone to heaven.

The past two weeks brought about all they had warned of and the portents of calamity that most investors had ignored — collapsing financial assets, crashing equity prices, margin loan calls, queues of newly unemployed outside Centrelink offices reminiscent of those old grainy photos taken of food and dole lines of early the 1930s (only baseball caps on backwards and sneakers replacing the fedora and black leather shoes), companies facing extinction and the prospect of a new, horrendous debt mountain overhanging the global economy.

And then was added the cream on the cake, the cracking of the paper gold market and a frisson of fear in trading companies that there would not be enough physical gold to satisfy everyone wanting to get their hands on the metal.

There wasn’t — at least, not readily available gold.

Gold supply chain has been disrupted

Britain’s BullionByPost, that country’s largest online supplier of gold and silver, commented recently that the precious metals supply chain was “creaking”.

The fact that investors are now coming to realise is that the large bars stored in central bank vaults cannot meet the needs of the panicking investors who want a 10oz bar or gold coins.

Over the weekend there were reports that most US online bullion retailers are out of stock of bars and coins, and those with some to sell have hiked their premiums (to as much as 12% in the case of one coins and one-ounce bars.)

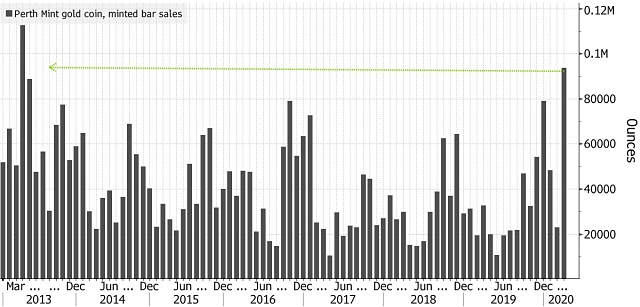

Meanwhile the Perth Mint reported is highest levels of demand since 2013.

Last month The Perth Mint experienced its highest level of demand in seven years.

Traders playing paper gold against physical were caught off guard, left scrambling for metal to meet counterparty demands.

The supply chain has been hit in three discrete zones: production, refining and transportation.

Mines are closing and exploration is being put on hold due to concerns about the COVID-19 virus.

For example, in accordance with a new Mexican Government directive, all mines in that country have been told to suspend operations. One of those complying is Newmont Mining which owns the Penasquito mine, producers of 129,000oz of gold per year (along with silver).

Also on the mining front, there are worries that the capital freeze could mean that junior gold exploration companies cannot get financing for their drilling, scoping and feasibility studies.

Three large Swiss refineries are currently closed due to COVID-19, removing around a third of the world’s gold refining capacity.

This not only impacts new gold but also the thriving business in processing large bars to more consumer-friendly weights.

Bullion retailers, even if they find stock to purchase, face the transportation issue: not many aircraft are flying these days, so air cargoes have to wait their turn.

In fact, there is a fourth problem in the supply chain. That is, large proportions of the world’s gold are held by central banks, funds and wealthy investors. And most of those can be expected to hold on to what they have.

Nervous for all the wrong reasons

There have been some days over recent weeks when the gold price has taken has a knock – some of them quite severe.

But then the same occurred in 2001 (after the implosion of dotcom) and 2007. In those cases, and now, it seems generally accepted that nasty margin calls have been behind this, physical gold being readily saleable if your financial back is up against the wall.

So, we have seen these short-term setbacks before.

In June 2007 the metal took a sudden sharp dive below US$650/oz, which gave the gold haters the chance to opine that the boom run was over. Six months later gold would finish the year at US$834.50/oz.

In March 2008 gold finally made it to US$1,000/oz.

Then, at the end of that month, there was another sharp plunge with the metal retreating to US$740/oz — but then would recover to, once again, end the year higher than what it had sat at on 1 January in spite of the 2008 Lehman Brothers collapse.

But everyone who was then losing faith in gold ignored factors that would sustain the yellow metal: global financial instability, rising costs in gold production along with insufficient (in number and size) of new gold discoveries to replace that metal which was being pulled out of the ground.

The March 2020 retreats were due mainly to what was politely called “liquidity events”, rather than any loss of faith in the yellow metal.

But there are reasons to be wary with gold

Warwick Grigor at Far East Capital says that for all the bullishness abroad, “investing in gold is not a slam dunk at the moment”. He argued that the gold price is jumping around from day to day in such a way that a real trend is difficult to discern.

He was also concerned that the Russian and Chinese central banks are ceasing official gold buying, and this could reduce short term expectations for the gold price.

Mr Grigor added the caveat that neither of those countries has a reputation for being truthful about their intentions.

However, in the case of Russia, Moscow is facing a crisis with the price of oil.

“Not buying any more gold at the moment is one thing, but what if the low oil prices force it to sell gold?”

“That could lead to a rush for the door,” he said.

It was also reported over the weekend that demand for gold in China is weak, with the metal now being sold at discounts to the benchmark price.

Ronald Leung, chief dealer at Hong Kong’s Lee Cheong Gold Dealers, told reporters that customers had other priorities.

“Gold is a luxury,” he said. “People would rather go to the supermarket than buy gold.”

Central banks have been a game changer

In 2001 Croatia received its allocation of what had been the national gold reserves of the by then dissolved nation of Yugoslavia, its share being 13.12 tonnes, and decided to turn that bullion into cash.

Croatia’s central bank at the time took the view that “the price of gold is unstable and depends on the unpredictable market, while deposits have fixed interest rates”.

The Croatians accepted US$277.78/oz for all their gold. When the gold spot market closed over the weekend in April 2020, gold was trading at around US$1,622/oz, a 483% increase on that 2001 sale price.

With gold currently at, or near, all-time highs in most currencies, the precious metal has recently been gaining against the US dollar as well.

The most recent Croatian central bank repo auction was done at 0.05%. Yes, interest rates these days are certainly predictable.

As of mid-2019, 90 sovereign countries had no gold reserves — including Canada, New Zealand and Norway (and Croatia, of course).

If any of those nations now has a change of mind, they could be leaving it a bit late: physical gold has become very difficult to put one’s hands on these days.

Since the global financial crisis, we have seen a dramatic change of heart by the central banks.

Who can forget the decisions from the late 1990s by the central banks of Britain, Australia, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and France to sell part of their gold holdings (and at the bottom of the market into the bargain, with the Swiss alone selling off 1,550 tonnes)?

Only the Germans and Italians resisted the temptation, which is why they are still the second and third largest holders respectively after the US — if you believe China’s low official figure (which not many people do).

By 2012, it had all changed. That year central banks bought 534.6t between them.

We also saw some central banks buy gold for reserve purposes for the first time (Jordan in 2015, for example), while others went into the market more aggressively, Kazakhstan doubling its gold reserves

Moreover, some governments became nervous about too much of their gold sitting in foreign (mainly British and US) vaults. Germany, then Austria and the Netherlands were the first to begin repatriating some of their bullion to home vaults. Last year the Dutch announced they were building a new secure repository, located inside a military base.

ETFs now have a challenge

Christopher Ecclestone, who heads the London-based research firm Hallgarten & Co, believes that the gold sector has been seen as a threesome: the physical market, the miners and the exchange-traded funds. For long, the ETFs have been touted as being “good as gold”.

That good-as-gold “fallacy” has come to grief with physical metal “becoming as rare as hens’ teeth” and global movements of bullion being stymied and disrupted by airline closures and suspensions of routes and quarantine measures, he continued.

“Then Bloomberg revealed that an apparently commonplace tactic of traders shorting gold futures in New York, against being long physical gold in London, had come horribly unstuck,” Mr Ecclestone said.

Suddenly the trades were mismatched with parties wanting physical delivery when the other side did not have, or could not get, physical metal.

“For the man in the street, though, such sophisticated trades elude them and they have plenty of time while in lockdown to ponder the value of cash money, the resilience of electronic (cashless) banking and how they pay for their daily bread.”

“One commented to us that ‘I have my gold coins’, to which we commented ‘Good luck buying a loaf of bread with that’.”

“In reality, silver coins are much more fungible when the apocalypse comes,” said Mr Ecclestone.