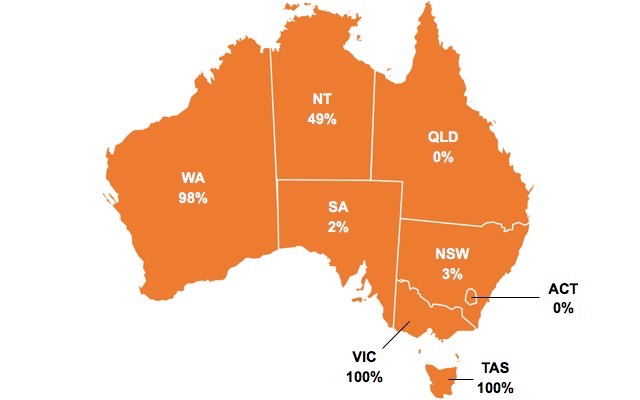

Fracking landscape in Australia by state and territory

The laws surrounding hydraulic fracturing in Australia vary by state and territory.

In a move that has attracted widespread criticism and intense opposition, the Western Australian Government has lifted its moratorium on hydraulic fracturing, paving the way for unconventional gas development in parts of the state.

The controversial action follows the Northern Territory’s lifted ban in April and South Australia’s decision to exclude the technology in just one region in November.

While this appears to signal a shift in perspective and priorities from government bodies, Australia remains largely divided on the topic with legislation in each jurisdiction differing from the next.

There isn’t necessarily a federal stance on fracking, although Prime Minister Scott Morrison is certainly “pro-fracking”.

Last year when he was the federal treasurer, Morrison was even accused of bullying states into agreeing with the practice by threatening to cut their GST distribution if they opposed.

The sentiment isn’t shared in some states, with Victoria especially being completely opposed to all onshore gas exploration at all.

The hydraulic fracturing technique

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, is a controversial method of extracting gas from typically hard-to-reach spaces like coal seams, shale or tight sandstones.

The process involves drilling into the ground before injecting a high-pressure fluid into the rock to fracture it apart and allow gas (or oil) to escape. Fracking is commonly carried out in stages along a horizontal borehole.

Frack fluids are generally made up of mostly water with added chemicals and ‘proppants’ like sand or tiny ceramic beads, designed to hold open the rock fractures.

It has been the subject of widespread criticism due to environmental concerns relating to the quantity of water used, as well as its suspected effects on groundwater and other pollution issues.

However, the practice has evolved over time with improved technology finding new ways to optimise extraction while minimising impact.

State and territory overview

Australia has mixed views on unconventional exploration and fracking, with each individual state and territory governing its own regulations.

Fracking bans by state and territory in Australia.

Here is the current lay of the land with regards to fracking and some of the ASX-listed companies operating in each region.

Western Australia

At the end of November, WA’s premier Mark McGowan announced the lifting of a blanket ban on fracking, although the practice will now only be permitted in 2% of the state.

The WA Government had imposed a state-wide temporary moratorium in September 2017 but following a 12-month independent scientific inquiry, it concluded that the “risk to people and the environment is low”.

However, fracking will still be prohibited in 98% of the state, with the ban only being lifted on existing onshore petroleum exploration and production titles.

“Fracking will continue to be banned in Perth, Peel and the South-West. National parks, the iconic Dampier Peninsula in the Kimberley and public drinking water source areas will also be declared off limits,” Mr McGowan said.

In addition, traditional owners and landowners will for the first time have the right to say “no” to any oil and gas production from fracking on their land.

“Banning fracking on existing petroleum titles, after the scientific inquiry found the risk from fracking is low, would undermine Western Australia’s reputation as a safe place to invest and do business,” Mr McGowan said.

“This is a balanced and responsible policy that supports economic opportunity, new jobs, environmental protection and landowner rights,” he added.

The independent inquiry by the Environmental Protection Authority made 44 recommendations with major changes to the existing regulatory regime including no fracking to be allowed within 2km of gazetted drinking water source areas or within 2km of towns, settlements or residents.

While a 2% allowance doesn’t seem like very much, this represents quite a vast area for the largest state in Australia. The existing onshore petroleum leases are located in the Kimberley, adjacent to the Dampier Peninsula area, an area north-east of Carnarvon and an area between Geraldton and Gingin.

One junior explorer that has welcomed the changes is Whitebark Energy (ASX: WBE), which believes its 4.4 trillion cubic feet to 11.6Tcf Warro gas project in the Perth Basin will benefit from fracking’s green light.

Following the ban lift, the company announced the legislative impediment to Warro’s development was in the process of being lifted. However, due to the WA Government’s decision to implement all recommendations of the scientific inquiry, Whitebark said no hydraulic fracturing activity may be able to occur until 2020.

“The WA Government should be congratulated for staring down activists who were pressuring it to ignore the science and ban hydraulic fracturing. But it should not ignore that same scientific advice by banning the use of this safe technique in certain areas and on new acreage releases,” Whitebark managing director David Messina said.

Northern Territory

WA’s move comes after the Northern Territory gave fracking the green light in April.

Following a separate scientific inquiry, the government lifted its own moratorium on 51% of the territory, with the remaining 49% still covered by the ban.

The inquiry made 135 recommendations, including stricter regulation and increased penalties for environmental harm, particularly regarding the use of water.

The territory government has endorsed all of the recommendations and said it would allocate $5.33 million over three years to putting the rules in place.

One gas producer that has been quick to publicise its delight in the ban lift is Empire Energy Group (ASX: EEG), which holds more than 14.5 million acres in the onshore McArthur and Beetaloo Basins.

In late October, the company announced it had applied to conduct a seismic program targeting the Velkerri shale formation, to be potentially followed by a drilling program.

Meanwhile, Baraka Energy and Resources (ASX: BKP) is currently seeking a farm-in partner to pursue opportunities in the Southern Georgina Basin, believing its acreage is in “good standing and represents an underexplored asset with potential to add significant value to the company”.

The company had encountered elevated hydrocarbon shows during the drilling of its McIntyre-2 well in 2011, but activities were suspended when the fracking ban was imposed.

“Whilst the last few years have been very trying for management and the shareholders, the company feel that there is however a more positive attitude returning to commodities and the junior end of the market in particular,” Baraka stated at the time of the ban lift.

“The potential for gas in the NT is still well publicised and the current political charged discussions on the potential shortages of gas and the high gas prices in the eastern states just adds further interest in the NT’s potential.”

Another junior explorer Armour Energy (ASX: AJQ) believes its 100%-owned NT tenements cover the “largest and most important part of the northern, central and southern McArthur Basin where the thickest and most oil and gas prone sections of the McArthur and Tawallah groups are present”.

Its McArthur Basin acreage has been estimated to hold 34.8 trillion cubic feet of best-estimate prospective gas resources within shale formations, although further exploration appraisal and evaluation is still required.

In a presentation released to the market last week, Armour said it was planning a regional seismic program as well as the drilling and appraisal of deep stratigraphic wells in the shale gas play.

Major gas player Santos (ASX: STO) also praised the NT’s changes with chief executive officer Kevin Gallagher telling shareholders at the company’s annual general meeting that Santos hoped to “get back on the ground there with exploration and appraisal activities as early as the dry season in 2019”.

“Moomba is a key hub for the east coast gas market and ideally placed to connect future Beetaloo production in the Northern Territory into the eastern and southern markets,” Mr Gallagher said.

South Australia

At the start of November, the South Australian government announced a 10-year fracking ban across the agricultural-rich Limestone Coast region in the south-east of the state.

South-east independent MP Troy Bell, who originally put forward the bill, told media that the community was “fearful” of fracking technology.

“It’s not that the south-east is against mining or gas extraction – it’s this technology, in that location over limestone where there’s aquifers that the entire region relies on,” Mr Bell said.

Fracking is still permitted in other areas of the state; however, this is subject to requisite approval processes.

In north-east SA, fracking has been undertaken in the Cooper Basin since the late 1960s in over 700 wells.

Some of Australia’s biggest gas players have gas projects in this basin, including Santos, Beach Energy (ASX: BPT), Cooper Energy (ASX: COE) and Senex Energy (ASX: SXY). All of these companies have been involved in fracking operations.

One junior player taking advantage of SA’s lenience on fracking in the Cooper Basin is Strike Energy (ASX: STX), which completed a multi-stage fracking program at its Jaws coal seam gas (CSG) project earlier this year. In mid-November, the company had reported its Jaws wells now producing continuous gas flows from both well heads.

Victoria

On the opposite side of the coin is Victoria, which in March 2017 became the first state in Australia to permanently ban all onshore unconventional gas exploration and development, including fracking and coal seam gas (CSG).

Conventional gas exploration is also currently prohibited, although this ban will expire in 2020.

One company getting especially riled up about the ban is junior explorer Lakes Oil (ASX: LKO), which has been going back and forth to court trying to overturn the decision.

The company, which considered the state-wide moratorium “unlawful”, was seeking damages including $92 million in past expenditure at its gas exploration sites and $2.6 billion in lost future earnings.

However, its claims were rejected in the supreme court in September and the company is now planning an appeal to be heard on 19 December.

Lakes’ former chairman Rob Annells, an outspoken advocate for onshore exploration and fracking, has expressed to Small Caps his dismay that the Victorian Government is still not reconsidering its stance on the practice despite improvements in the technology.

“To just ban fracking without checking the science or even allowing for [the technology] to change, I think, is very short-sighted,” he said.

“Here in Victoria, we used liquid nitrogen – it’s more expensive but you’ve got less damage using something like that.”

“It’s crazy. We did 11 fracks here in Victoria. Nobody got hurt, there was no damage, nothing wrong – the department didn’t even send anybody down to have a look,” Mr Annells said.

Tasmania

The Apple Isle introduced its moratorium on fracking in 2014 and this was reconfirmed in October this year, with the ban now in place until 2025.

However, Tasmania will continue to permit unconventional exploration, with the government’s mineral resources department stating its uncertainty that economically viable unconventional hydrocarbon resources even existed in the state, and that this could “only be determined through further private sector exploration”.

New South Wales

While NSW does permit unconventional exploration, the state government considers itself as having the “toughest” regulations in Australia – specifically in relation to CSG.

In 2014, amid pressure from environmentalists and farmers, the NSW Government froze new CSG exploration licences and introduced exclusion zones, making residential areas in 152 local government areas of the state, including Sydney, “off limits” to new CSG activity.

The exclusion zones also ban CSG activity within a 2km buffer around any future residential areas or critical industry clusters.

While the freeze on exploration has now been lifted, no new licences have been granted and the state government has even bought back some exploration blocks it had previously awarded.

Junior company Metgasco (ASX: MEL) had been exploring for CSG in the Northern Rivers region of NSW before it accepted a $25 million offer from the NSW Government to withdraw from its exploration licences in 2015, following pressure from local green groups and farmers to shut down fracking activities in the region.

So instead, it headed north to more lenient Queensland where it was awarded two prospecting licences in the south-west of the state. The company currently has plans to drill one of two identified conventional prospects in the second half of 2019.

Queensland

By contrast, the sunshine state is more broadly “pro-development” with no moratoriums on unconventional gas exploration and development currently existing for any regions.

As a result, most unconventional gas produced in Australia comes from here, with the state’s Bowen and Surat basins being the main producers of CSG.

Queensland hosts three major projects involving the conversion of CSG into liquefied natural gas (LNG) for exporting: the Santos-operated Gladstone LNG project, Origin Energy’s (ASX: ORG) Australia Pacific LNG and Dutch supermajor Shell’s Queensland Curtis LNG projects.

Other operators in the state include CSG explorer Comet Ridge (ASX: COI), which holds a 40% majority stake in the Mahalo CSG project in joint venture with Santos and Origin Energy. With an estimated 172 petajoules of 2P gas reserves, this project is considered one of the largest undeveloped gas resources on the Australian east coast.

Emerging developer Real Energy (ASX: RLE) recently conducted a multi-stage fracture stimulation on two wells at its Windorah gas project, where it is hoping to unlock a potential 3C resource of 672 billion cubic feet of gas.

The company also recently secured a gas processing deal with Santos and Beach Energy to link its three Windorah wells to the joint venture’s Cooper Basin gas network and process gas at their facilities in Moomba, SA.

Australian Capital Territory

No fracking restrictions exist in the nation’s capital either, but that is also due to there being no gas reserves here.

In addition, under the Australian Capital Territory’s established sustainable energy policy, it is planning to be 100% run on renewable energy sources by 2020. Increasing figures have so far estimated that the territory will reach 78% renewable electricity by the end of 2018.