Fracking. The word itself can lure interest, as well as opposition. It has even divided the nation politically.

This gas extraction method has been used since the 1940s, although it has truly come to the fore in the last decade thanks to North America’s shale oil and gas boom.

The technology has evolved over time, with recent innovations even bringing it in line with the modern world of centralised and digitised operations.

But no matter how much the technology changes, will it ever be supported enough to unlock Australia’s potentially massive unconventional gas resources?

What the frack?

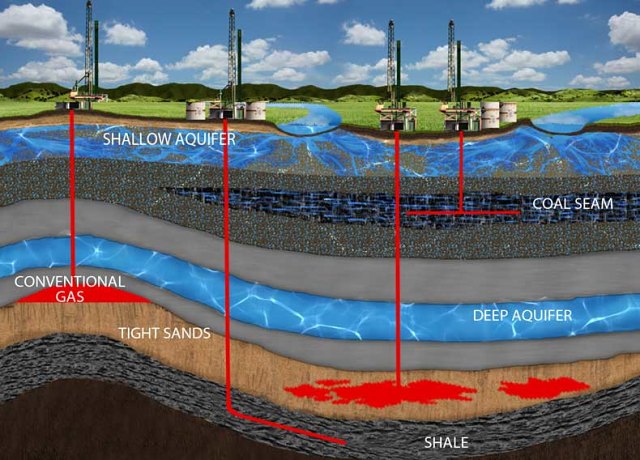

Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracture stimulation or shortened to ‘fracking’, is a method for extracting unconventional oil and gas that occurs in more difficult-to-reach deposits, such as in shale, coal seams and tight reservoirs with low permeability.

The process involves drilling into the ground before a high-pressure water mixture is injected into the rock to fracture it apart, allowing the oil or gas to be released.

This water mixture, referred to as ‘frack fluid’, also includes chemicals and proppants designed to hold open these channels, or ‘fractures’, so that the gas can flow more easily to the wellbore. Sand is the most commonly used proppant, although tiny ceramic beads can also be used.

The chemicals in the fluid are similar to household chemicals, such as acids, borate salts, sodium chloride and sodium carbonate. These additives help the fluid’s ability to transport the sand by reducing friction, removing bacteria, dissolving certain minerals and preventing scale build-up.

Why the hype?

Fracking is a controversial method for a variety of reasons.

Environmentalists believe the biggest concern is the vast quantity of water required for the operation. Another is the potential for chemicals used in the frack fluid to escape and contaminate nearby groundwater.

According to the Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association, less than 1% of the fluid in Australian fracking operations are chemicals – the rest is water and sand.

The oil and gas industry has also disputed contamination claims in a broad sense, arguing that any pollution incidents were rather the results of bad practice.

Other arguments against the extraction method include noise and air pollution, and it has also been linked to an increased risk of earthquakes.

On the other hand, advantages include the ability to access more natural gas resources without needing to drill as many wells (as the technology increases flow from a well), in addition to reducing a reliance on coal, creating employment opportunities and ultimately – by generating an abundance of oil and gas in the market – making fuel cheaper.

In the US, the method was touted as an aid that saved the economy as before the shale revolution, the nation relied heavily on foreign oil.

In Australia, however, the cons have so far outweighed any pros at least at state government levels, despite the country’s looming gas shortages.

Evolving technology

Over the past seven decades, hydraulic fracturing has been used commercially to enhance oil and gas production in more than 2 million wells worldwide.

It is now used in about 90% of all new gas wells in the US. In Australia, more than 700 wells in the Cooper Basin alone have been fracked since the late 1960s.

As ideas changed and the technology evolved, different types of frack fluids and proppants have been trialled.

Cryogenic fracking, where water is replaced by fluids such as liquid nitrogen or liquid carbon dioxide, is one method being investigated. While it is less environmentally damaging in terms of water usage, it is even more expensive for an operation that is already capital-intensive.

Multi-stage stimulations

Another way the technology has changed is the undertaking of multiple stages of fracture stimulations in the one well, rather than a single stage.

Texas-focused oil and gas junior Winchester Energy (ASX: WEL) currently derives production from its fracture stimulated White Hat 20#2 oil well in the US states’ Permian Basin. It is also evaluating whether to launch a fracking program at its nearby White Hat 39#1L well.

Winchester managing director Neville Henry told Small Caps that the “most effective wells are long horizontals with 20 to 30-stage fracks”.

“Natural, fine sand and lots of water flushing the sand deep into the formation is the best way,” he said.

“Winchester is looking into the future a little, as oil prices rise, into using the technologies to develop stacked intervals in the Wolfcamp D and Strawn formations in its Permian Basin Eastern Shelf acreage,” Mr Henry added.

He also noted that horizontal wells need to be drilled “in particular directions across the minimum stress, not just to intersect more natural fractures but to frack in a way that the induced fractures stay open for oil molecules to pass through”.

Alignment flow technology

This is an idea that Real Energy (ASX: RLE), in collaboration with Professor Raymond Johnson Jr at the University of Queensland, is evaluating.

The company’s recently drilled and fracked Tamarama-2 and Tamarama-3 wells at its Windorah gas project in Queensland have incorporated new well designs that enhance productivity from the wells through an improved alignment between the hydraulic fracture and the wellbore.

“What you want is the fracture to go through the rock in the way the natural stresses run – that way you can break up the rock easier and you’ll get a straight line as opposed to a windy road,” Real Energy managing director Scott Brown told Small Caps.

When the fracture isn’t straight, this makes for a less efficient pathway back to the wellbore, he explained.

“The way the rocks are orientated and the stress that comes from the tectonic plates are quite different in Australia and therefore, the techniques that work in the US don’t necessarily work effectively in Australia,” Mr Brown added.

“A lot of the techniques have to be modified and we have spent a lot of time and research into coming up with new techniques that will work in Australian conditions like the Cooper Basin.”

“This alignment flow technology is really trying to get the stress regime to work for maximum [benefit], or to optimise the flow back to the wellbore,” Mr Brown said.

IoT based technology

In recent months, Canadian company Rice Investment Group made international headlines when it invested in fracturing software developer Cold Bore Technology Inc, which has developed the first Internet of Things (IoT) based electronic completions recorder and remote frack operating system.

The technology, known as “SmartPAD”, digitises well completions to streamline and track operations. According to Rice, it enables hands-free wellhead operations, reduces human error and labour costs while also improving field safety by removing personnel from high-pressure zones.

Essentially, it replaces a lot of manual work for operators and service companies by digitising the wellhead as well as using blockchain-based smart contracts to track the data that is gathered automatically in the field.

However, this idea of ‘centralised technology’ is nothing new, even though this may be an improvement to it.

Rob Annells, former Lakes Oil (ASX: LKO) chairman and vocal advocate for onshore gas exploration, believes it won’t be a game-changer in Australia due to current legislation.

“Thanks to the government, we are 20 years behind in technology here. Whatever you’re looking at is going to look fantastic compared to what we’ve got here,” Mr Annells told Small Caps.

Brown also weighed in, saying that as Real Energy fracks 2.5km under the ground, personnel on the surface isn’t a major concern.

“You’ve got 2.5km of rock between you and the surface, so it doesn’t really matter if you have the location right on side or 20km away – it’s not going to make any difference,” he said.

While this may not be as revolutionary as it first appears to be, it is an example of the industry moving with the digital age and points to the diverse capabilities of blockchain technology.

Inconsistent legislation

Annells believes the reason the Cold Bore technology seems so revolutionary is because Australia is “lightyears” behind the US and Canada in terms of unconventional gas development.

Despite its potential, Australia drills far less unconventional wells, partly due to the nation’s mixed views on onshore gas exploration and fracking. Even the government is inconsistent with different rules in each state and territory.

In March 2017, Victoria became the first state in the country to permanently ban onshore unconventional gas exploration and development, including fracking.

South Australia has had a 10-year moratorium in place since late 2016, although this only applies in the south-east of the state in a region with a large agricultural and cattle grazing sector.

Tasmania has a moratorium in place on fracking until March 2020, although shale oil and gas exploration is still permitted, and New South Wales has just applied certain restrictions on the extraction method.

A 12-month moratorium was imposed in Western Australian last September although the government is still reviewing a report by an independent scientific inquiry before making its decision on the practice.

Meanwhile, the Queensland government is much more supportive of the industry, with the commercial production of coal seam gas having grown rapidly in the last 20 years, specifically in the Bowen and Surat basins.

Unconventional operators in the Northern Territory are now also looking to get back on track with exploration and development plans after its fracking moratorium was lifted in April.

Although, the lift came with the condition that all 135 recommendations of a scientific inquiry would be implemented in full. These rules included stricter regulation and increased penalties for environmental harm, particularly regarding the use of water.

Australia’s fracking future

So, will Australia eventually be on board with the technology as it evolves? Mr Annells doesn’t think people will change their perceptions, but Mr Brown does.

Brown said there is “no doubt” the development of fracking in Australia has slowed compared to North America, but believes “in terms of technology, we’re starting to make headway”.

“Fracking techniques are getting better and better. We can use less water for the same result, for example. Each generation is getting more and more efficient at doing it,” he said.

“Every state government has had a fracking inquiry and virtually all the inquiries have come to one conclusion – that fracking is safe if it’s done correctly.”

“I think it has taken the edge off the politics because they’ve got cover from independent experts that have all said there are no issues. More people, certainly at government level, are recognising that there are not any issues with fracking,” Mr Brown said.