Cobalt supply chain needs transparency as human rights violations continue in DRC

Human rights violations continue in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Calls for transparency along the cobalt supply chain have intensified as human rights violation allegations out of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) continue to proliferate.

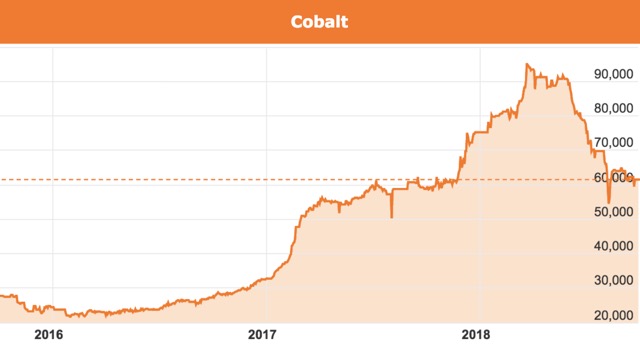

Currently about two-thirds of the world’s cobalt arises out the DRC. However, due to the region’s intense poverty and the mineral’s soaring price, thousands of impoverished Congolese have flocked to the cobalt rich areas to secure an income.

Under cover reporters recently managed to capture video footage of the artisanal “mining operations”, which are merely hand dug holes that don’t comply with even the most basic safety standards.

Those seen digging the make shift “mines” are men, women and children and the lack of safety and regulation have resulted in numerous fatalities.

It has been touted for some time that most people who own a smart phone, laptop or other electronic device cannot be 100% sure it hasn’t involved child labour at some stage from the DRC.

Speaking with Small Caps, Northern Cobalt (ASX: N27) managing director Michael Schwarz said it is a complex problem – as the local Congolese need the income, but the authorities in the region have failed to implement regulations around the artisanal operations.

The situation isn’t made easier by the faster than expected uptake of electric vehicles around the world, which require cobalt in the lithium-ion battery.

Since 2011, around 5 million electric vehicles have been sold around the world. However in the last six months alone 1 million electric vehicles have been purchased.

Removing cobalt in lithium-ion batteries

For those unfamiliar with the lithium-ion battery, it has three primary components: anode, cathode and the lithium electrolyte.

While the anode is usually made from a processed graphite, the cathode is a combination of several formulas with the more dominant ones, particularly in electric vehicles, comprising cobalt, nickel and manganese in various ratios.

The mineral has now been designated as critical with the estimates that the battery market is swallowing up more than 45% of global cobalt supplies.

In an attempt to alleviate the pressure on supplies, there have been efforts made to develop batteries without cobalt.

Although some of the fledgling technology looks promising, Mr Schwarz said it will be at least another decade before the alternative batteries have any real impact.

Mr Schwarz pointed out the cobalt-free batteries would need to be tried and tested and found commercially viable. He added battery manufacturers would then need to spend billions on building giga factories based on the new technology.

In the interim, the insatiable demand for batteries continues to surge, with Umicore’s chief executive officer Marc Grynberg claiming cobalt-free batteries would not be around for at least the next three decades.

While there are fledgling cobalt-free batteries under development, major manufacturers like Tesla have reported efforts to reduce the amount of cobalt in their lithium-ion battery formulas, but Mr Schwarz said eliminating it altogether was not possible at this stage.

Cobalt is a key ingredient in three of the five primary lithium-ion battery formulas due its ability to safely boost the battery’s energy density from around 100 watt hours per kilogram to 250Wh/kg.

Surging cobalt demand

Additionally, Mr Schwarz pointed out that even though cobalt has been reduced in several dominant lithium-ion battery formulas, demand for the mineral remains high based on the soaring global consumption of electric vehicles.

He also noted that other markets for cobalt continue to grow and firm and are predicted to continue doing so – placing even more pressure on the metal’s supply side.

Cobalt consumption is increasing in alloy markets and Mr Schwarz said Northern Cobalt had even been approached by end-users in the ceramics industry where cobalt is used as a pigment.

Demand for the mineral is predicted to swell from 53,000t in 2015 to more than 120,000t by 2025.

With demand increasing in most of cobalt’s primary markets, the pressure on supplies don’t appear to be ending any time soon.

Supply chain transparency needed

Key end users such as Apple, Samsung and Panasonic are under increased burden from socially conscious consumers to prove their product is made from ethically sourced minerals.

However, Mr Schwarz said they can’t be 100% certain the battery within these goods does not comprise unethical cobalt.

Major cobalt producers in the DRC have affirmed their operations comply with human rights regulations; however, Mr Schwarz said that unethically mined cobalt can be mixed in with ethically sourced cobalt during the refining process, particularly in China which controls approximately 85% of the world’s cobalt supply.

This obfuscation means that most end-users like electronics manufacturers and electric vehicle makers can never be 100% sure the cobalt in their product’s battery isn’t from child labour.

Mr Schwarz said sourcing cobalt directly from regulated jurisdictions such as Australia can temper part of the problem for a short spell – taking the pressure off the DRC. But, he pointed out this does not help those in the DRC that depend on cobalt for an income.

“The building of that transparency in the supply chain I think is the critical issue that needs to be done,” Mr Schwarz explained.

“The DRC does need the source of income, but it needs to be a push from the end-user to make the institutions within the DRC to change their practices.”

To reduce the amount of unethical cobalt on global markets, Mr Schwarz said it is more costly but companies could carry out random assessments on the cobalt they purchase to determine its origins.

Mr Schwarz added tamper proof packaging with bar codes that are scanned at every stage of the value chain can also help mitigate the issue.

However, until these practices are implemented, no electronic device owner in the world can be assured that device’s battery does not include material originating from child labour out of the DRC.