Boeing and FAA lose more than money in plane crash response

The latest Boeing incident could have far greater implications on US regulators operating in other fields.

Apart from the very human side of the tragic crash of the Ethiopian Airlines 737 Max 8 with the loss of 157 lives, there have been a number of dramatic developments in the fortunes of plane maker Boeing and the US aviation regulator, the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA).

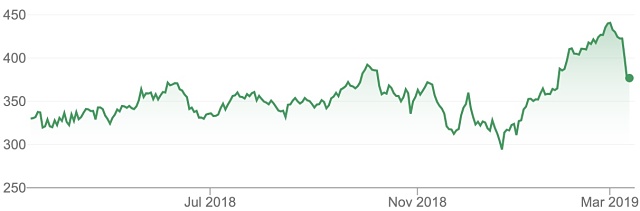

For Boeing, two tragic crashes of its most sought-after new plane resulted in the shedding of almost $38 billion of share market capitalisation as investors reacted to the potential losses for the world’s biggest maker of passenger jets.

Boeing’s share price takes a hit.

The damage caused to the FAA was possibly even greater as it continued to insist that the 737 Max 8 planes were safe to fly, even as aviation authorities all around the world were progressively grounding them.

By the time the FAA and US Government finally acted to ground the planes, they were several days too late to the party.

Fresh data excuse doesn’t hold water

The excuse that some new data had come in from the Ethiopian Airlines crash that showed similarities between it and the Lion Air crash was very difficult to swallow, given that other aviation regulators had come to that conclusion several days earlier.

It also didn’t tally with reports that US pilots had reported issues with the plane which appear to have been ignored or not acted on.

As for acting out of “abundant caution’’ in grounding the planes, the time for that was after the first crash, not the second and certainly not after most other regulators had already acted.

It was a staggering and unprecedented development given that the FAA – like most US regulators – has assumed and effectively been granted a position of global leadership for decades.

That carefully established leadership position was effectively ended as first China and then a host of countries initially including France, Germany, Ireland, Singapore, Australia, Indonesia, The Netherlands and the UK joined in grounding the Max 8 planes.

Some even prohibited the planes from flying across their airspace, eventually covering most of Europe.

That meant that countries still flying the planes – such as Canada and the US – could only fly them domestically anyway because they couldn’t land anywhere overseas.

Eventually even Canada grounded the planes adding its name to a list of more than 40 countries, leaving the US as the global laggard and the polar opposite of a leader.

Americans wanted the planes grounded

Worse still, US passengers and even the big US unions covering airline flight attendants were trying to avoid flying on the planes, fearing another fatal crash after the Ethiopian one and the very similar crash less than five months earlier after a Lion Air 737 Max 8 plunged into the Java Sea off the coast of Indonesia, killing all 189 on board.

Both crashes occurred not long after take-off in almost brand-new planes with the most likely culprit at this stage the MCAS system (Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System), which can force the nose down when airspeed indicators show that there is a potential stall.

Leaving aside the technical merits and potential defects in the plane, including a lack of effective pilot training and potential failures of airspeed indicators, the reason that highly respected aviation regulators such as those in the UK took action is precisely the same as the reason the FAA didn’t take any action.

That is, the lack of data coming from the two similar crashes was used as a reason to keep the planes flying for the FAA while the other regulators saw that lack of data as a good reason to ground the planes until the data was in.

It is the difference between a “we don’t know that it is not safe” attitude and a “we know it is safe’’ attitude.

The flying public are in this second camp too – they want to be absolutely sure that everything that can be done to make their trip safe is being done, even if that means disruptions by grounding a type of plane until the results from the two crashes are in.

Software changes show there is a problem

Amid all of this turmoil, Boeing and the FAA effectively admitted there were problems with the Boeing 737 Max 8 by announcing changes to the plane’s anti-stall software and faulty sensor readings that had been linked to the Lion Air accident.

The updates are aimed at preventing a malfunctioning sensor like the one on the Lion Air jet from activating the MCAS pushing down a plane’s nose when it’s not needed.

The software update and other changes limit the number of times the system kicks in and the magnitude of force it exerts.

Boeing will use inputs from two sensors that measure a plane’s profile against oncoming wind, instead of relying on a single one, to assess the threat of an aerodynamic stall.

The manufacturer also plans to make standard on pilot displays an indicator showing when the two sensors have conflicting data.

Will other US regulators lose authority too?

It may be early to speculate but there is certainly a possibility that US regulatory leadership in other areas could be undermined.

For example, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies around the world routinely run different phases of clinical trials and present them to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to prove the safety and effectiveness of new drugs or medical devices.

Once the FDA gives a new drug the thumbs up, it is usually only a matter of paperwork to get approval in other markets as their regulators examine the FDA process and allow the drug in their markets.

That approach makes sense because of the FDA’s great reputation and also because the US is the world’s biggest market for drugs, making it a logical first stop.

However, it is not impossible to imagine a scenario in which drug and medical device makers might seek approval in other markets first through European or Japanese regulators, for example – a path that some are already taking but which could become more common.

That is the danger if the gold standard such as the FAA or the FDA is seen as being slow to act, unwieldy or behind the curve.

Regulatory leadership is something that is hard won over many decades but as the Boeing 737 Max 8 debacle shows us, it can be eroded much more quickly.