Australia has taken the bold step of approving gene editing technology CRISPR in the hopes of developing breakthrough cures for a host of ailments and diseases.

Otherwise known as “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats”, CRISPR is a novel gene-editing technology that exploits quirks in bacteria immunity to edit genes in other organisms.

The new technology has spurred dozens of labs around the world into developing the next generation of medical breakthroughs.

To ensure the biotech industry comes into port both ethically and commercially, Australian authorities have decided to regulate CRISPR and to approve it for use as of October this year.

In a public statement, the Australian Government’s Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR) said that “most genome editing techniques will be explicitly regulated”.

However, the technique known as SDN-1 will be excluded because, based on scientific evidence, SDN-1 organisms present no different risk than organisms carrying naturally occurring genetic changes.”

The government agency added that “organisms modified using SDN-1 cannot be distinguished from conventionally bred animals or plants, and there is no evidence that they pose safety risks that warrant regulation.”

As a result, CRISPR gene editing has been approved for plants, animals, and human cell lines under the condition that new genetic material is not created.

Australian regulators said that the decision was the result of an extensive review of the country’s regulation overseeing gene editing technology.

Past, present and future of CRISPR

CRISPR was first discovered in 1993 by Francisco Mojica, a scientist at the University of Alicante in Spain.

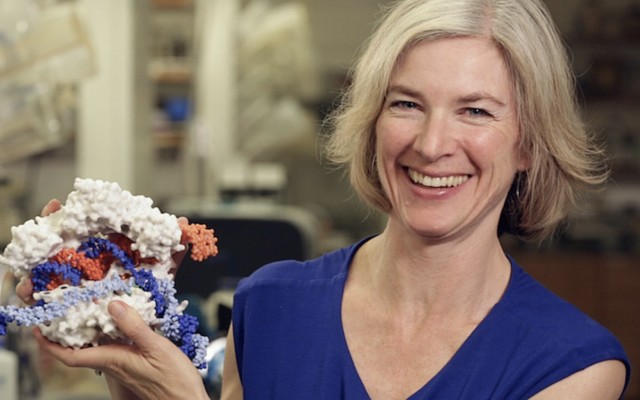

In addition to Professor Mojica’s work, US-based scientist Jennifer Doudna has made more recent contributions to the so-called CRISPR revolution.

The CRISPR gene editing tool works by targeting DNA at a specific target site and removing whatever part has been identified as causing undesirable issues in the organism – or vice versa, adding genetic material to create desirable traits.

More recently, a team of scientists from the Oregon Health & Science University successfully used CRISPR to “snip off a defective gene” in human embryos which causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a hereditary coronary disease.

Gene editing allows scientists to precisely target, cut, delete and edit parts of the genome they want to change.

With this field of biotech growing rapidly in parallel to other innovations as stem-cell research, gene therapy and immuno-oncology, CRISPR is already being deployed to augment plants, animals and even humans.

Just last year, Chinese scientist He Jiankui shook the world of biotech by announcing the creation of the first gene-edited human twins using CRISPR technology to make them HIV resistant.

Previous CRISPR restrictions

Previously, the use of CRISPR for research purposes was restricted because the techniques were governed by the same rules as conventional genetic modifications, which require approval from a biosafety committee accredited by the OGTR.

With the approval now received in Australia, a slew of labs throughout the country will work on various applications of the technology, but must wait until 8 October 2019 when the amendment comes into effect.

But with such scientific breakthroughs offering a whole host of advantages, benefits and efficiencies, is CRISPR too good to be true?

CRISPR criticism

Despite its highly-acclaimed potential, CRISPR is also facing strong criticism – especially after the recent decision by Australian authorities not to regulate CRISPR gene editing tool, SDN-1.

The OGTR has chosen to regard particular types of CRISPR techniques as a form of genetic “mutation” as opposed to genetic “modification”, which implies a perceived reduction of risk to patients and the natural environment.

Critics have been up in arms about this move due to its attempt to bypass existing regulation covering medical drugs produced with genetic modification. Medical products made with GMOs are regulated differently in contrast to GMOs created for agriculture and food purposes that must comply with health and safety regulations.

Medical GMO products are typically subjected not only to extensive pre-clinical efficacy testing, but also, a rigorous regulatory system, including multiple phases of clinical trials before products are considered market ready.

Critics argue that the OGTR has effectively given biotech companies the green light to develop potentially harmful products without enough oversight.

Several Institutional Biosafety Committees have opposed the deregulation of CRISPR on safety grounds, including the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC), Victoria University, Children’s Medical Research Institute and Children’s Hospital Westmead and the University of Wollongong.

“We are concerned that the OGTR has ignored the advice of so many biosafety experts, instead relying on advice from scientists from institutions with clear commercial conflicts of interest and partnerships with Monsanto, when making its recommendations,” said Louise Sales, coordinator of Friends of the Earth’s Emerging Tech Project.

“These techniques are quite clearly genetic engineering. The fact that the OGTR is even considering not regulating them shows how captured it has become by biotechnology industry interests,” she said.

In response, the OGTR says that genetic edits made without templates are “no different from changes that occur in nature”, and therefore, do not pose an additional risk to the environment and human health. The agency also vowed that gene-editing technologies that do use a template, or that insert other genetic material into the cell, will continue to be regulated.

However, the OGTR’s proposal has not yet crossed the finish line of being legalised and must still be approved by Australia’s next parliament after the upcoming general election.

Meaning there is still a possibility that a new government could reject the proposal.

When looking further afield, it’s clear that various governments are taking different ethical positions in relation to CRISPR.

Regulatory arbitrage

In July 2018, the European Union decreed that gene editing techniques such as CRISPR pose similar risks to older GM methods and need to be assessed for safety in the same way.

Australia’s neighbour New Zealand also plans to impose strict restrictions on gene editing, which could potentially create friction within the existing Trans-Tasman trade routes involving livestock and agri-business.

Over in the US, the country’s Department of Agriculture excluded genome-edited plants from regulatory oversight altogether.

Clearly, some countries are seeing CRISPR from entirely different perspectives and are making rather different risk assessments as a result.

Hitting the ground running

If fully approved, the OGTR’s verdict could eventually mean that a series of new GM animals, plants, and microbes will be introduced into the food chain with no safety assessment and, potentially, no labelling.

These include “super-muscled pigs”, non-browning mushrooms, and wheat with powdery mildew resistance. While Australia and the US are arguably leading the charge into the new frontier of gene editing, other countries such as New Zealand and the EU are being far more cautious.

As with most new biotech innovations, there is a cavalry of both critics and supporters claiming a variety of costs and benefits.

One thing is certain – given the different approach being taken by regulators globally, consumers in different regions will be exposed to GM products at different intensities with international trade set to have yet another stumbling block when it comes to trade agreements and health and safety standards.